Adolescents/Adults with Neglected Congenital Muscular Torticollis. Case Description: An Adolescent with Problems Due to Neglected CMT

Anna Maria Ohman

Health and Rehabilitation/Physiotherapy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg

*Corresponding Author: Anna Maria Ohman, Health and Rehabilitation/Physiotherapy, University of Gothenburg, Gothenburg, Sweden.

Received: 28 April 2025; Accepted: 16 May 2025; Published: 25 May 2025

Article Information

Citation: Anna Maria Ohman. Adolescents/Adults with Neglected Congenital Muscular Torticollis. Case Description: An Adolescent with Problems Due to Neglected CMT. Archives of Physiotherapy and Rehabilitation. 8 (2025): 08-14.

Share at FacebookAbstract

The aim is to describe an adolescent with neglected Congenital Muscular Torticollis (CMT) and to discuss some difficulties for adolescents/adults with neglected CMT. Even though CMT is mostly discovered in infanthood, some individuals do not get treatment in time. For older children/adolescents/adults with a visual muscular cord tightness in the sternocleidomastoid muscle, surgery is mostly a requisite for physical therapy to work. Surgery for CMT is nothing new but there seems to be a lack of knowledge about it, especially for older children, adolescents, and adults. When CMT is not treated, the head remains tilted toward the affected side, there is restricted motion in the neck, often an elevated shoulder on the affected side, some lateral shift of the head, pain, and facial asymmetry. Early surgery is preferable. However, adults with neglected CMT can benefit from surgery; they can get increased neck motion, a straight head position, less pain and better well-being. Surgery should be offered regardless of age as it can make an important difference to the individual. In the described case an adolescent with considerable effects of neglected CMT felt that she had gained a new life after surgery.

Keywords

Adolescent/adult, neglected CMT, surgery, physical therapy

Adolescent/adult articles, neglected CMT articles, surgery articles, physical therapy articles

Article Details

Introduction

Congenital muscular torticollis (CMT) is a common musculoskeletal abnormality in infants. The head is typically titled towards the affected sternocleidomastoid (SCM) muscle, and the chin is rotated towards the opposite side. Stellwagen et al found that 16% of newborns had torticollis (1), which suggests a higher than previously reported incidence of 0.4%-2.0% (2). CMT can cause limited range of motion (ROM) in both rotation and lateral flexion of the neck. Infants with CMT have an imbalance in muscle function around the neck; it has been found that lateral head righting on the contralateral side is weakened compared with the affected side (3, 4, 5, 6). This imbalance in the lateral flexor muscles in the neck has not been found in healthy infants in a control group (7). It is of great importance to reduce the muscular imbalance in young infants with CMT (6). When there is a remaining imbalance in muscle function it can be hard for a child to achieve symmetric head posture. CMT treated in infanthood gives good or excellent results for about 90-95% of cases, only 5% need surgery (2, 8). The indications for surgery are persistent head tilt, limited passive ROM (PROM) in rotation and/or lateral flexion, and a tight band or tumor in the SCM muscle (9). During the time of skeletal growth, a persistent CMT can affect facial growth, resulting in more or less obvious facial asymmetry (10, 11, 12, 13, 14). The head tilt itself is assumed to cause the facial asymmetry (15). With early treatment most of the facial asymmetry gets corrected during the first years after surgery (16, 17, 18). After skeletal growth has finished it is less likely to improve facial asymmetry. Ippolito and Tudisco found no improvement in facial asymmetry in eight patients all above 20 years of age (19).

Some cases of CMT are undiagnosed or untreated until adolescence or adulthood, resulting in neglected CMT (20). When CMT is neglected and the individual has become an adolescent or adult before getting treatment, surgery is more often needed (16). Patients with neglected CMT often have head tilt already during infancy/childhood but for some reason get no treatment (21). When CMT is not treated it is common that the shoulder on the affected side is elevated (21). Neglected CMT can give neck and/or shoulder pain (22) which improves after surgery (20). Among adolescents/adults with neglected CMT it is not uncommon that they have a history of meetings with pediatricians, physical therapists (PT) and other health care professionals who say that nothing can be done about CMT. For surgeons, PTs and others with knowledge of CMT and surgery, it is easy to recognize a case in need of surgery as there is often an obvious visual muscular cord tightness on the affected side. Adults with neglected CMT can benefit from surgical treatment (23, 24, 25, 26, 27) which should be corrected regardless of age (24, 25, 26). Both head tilt and lateral shift of the head can markedly improve after surgery (20, 24) giving satisfactory results (27, 28). Torticollis in the neck may cause secondary scolios in the back and release of the contracted muscle can be beneficial for scoliosis (24, 25, 29,30). Choi et al showed significant improvement in scoliosis in all age groups after surgery for CMT (24). There are benefits with earlier surgery as younger age groups showed significantly more improvement than the older groups, i.e. above 18 years of age (24).

Cheng and Tang´s scoring system for assessment of clinical and subjective outcome in CMT, can be used before and after surgery (8, 27, 31). The scoring system includes: rotational deficits (degrees), side flexion deficits (degrees), craniofacial asymmetry, residual band, head tilt, and subjective assessment (cosmetic and functional). After surgery scoring also includes scars. There are four levels: excellent, good, fair, and poor (8) (table I).

Table I: Levels and scores on Cheng and Tang´s scoring system for assessment of clinical and subjective outcome in CMT. Scores after surgery also include scars and therefore have a higher range.

|

Level |

Scores before surgery |

Scores after surgery |

|

Excellent |

16-18 |

17-21 |

|

Good |

Dec-15 |

Dec-16 |

|

Fair |

06-Nov |

07-Nov |

|

Poor |

<6 |

<7 |

In 2013 guidelines for CMT were published by the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA). They developed CMT classification grades and a decision tree with grades from 1 to 7. Grade 1 is early mild and grade 7 is late extreme (32). APTA upgraded the guidelines both in 2018 and in 2024. CMT classification grades and the decision tree were updated with one more grade: grade 8 is new, which is very late (33). However, there is a lack of information about treatment after surgery and neglected CMT (32, 33, 34).

After surgery the patient wore a brace both day and night. Repetitive cervical ROM training in the early postoperative period is very important (20). Physical therapy is carried out three times a week in a clinical setting (35): stretching, mirror exercises etc., to reestablish perception of midline through integration of visual, vestibular, and proprioceptive systems (36). A home program with daily training is given, depending on age the patient will need more or less help from parents. Physical therapy should be continued as long as needed (35). The affected side is almost always stronger after surgery and strengthening the opposite side is necessary (31). In the beginning the opposite side often needs to be trained until it gets stronger than the affected side. This imbalance will even out after a while when the training is ended.

Case

A 17-year-old adolescent with left-sided congenital muscular torticollis came to our clinic for a second opinion in August 2019. According to CMT classification grades and the decision tree from 2018 she had grade 8 i.e. very late (33). On Cheng and Tang´s scoring system for assessment of clinical and subjective outcome in CMT, her scores were zero before surgery, i.e., poor in all categories (8, 27, 31).

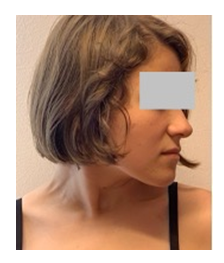

When the girl was a toddler, her mother was told that nothing could be done about the condition. At the age of 17 the SCM muscle on the left side was hard and unusually underdeveloped, with an obvious muscular cord tightness that was not stretchable (figure 1). There was limited motion in rotation of the neck bilaterally both actively (figure 1 and 2) and passively. PROM in rotation was measured with an arthrodial protractor (2, 7, 8, 21), rotation towards the right was side 60° and towards the left side 50°.

There was also a remarkable difference in lateral flexion (figure 3 and 4). When she tried to straighten up her head, there was a lateral shift of the head towards the right (figure 5) and the short SCM muscle caused pain.

She had facial asymmetry and scoliosis in her back due to neglected CMT. At our first meeting it was obvious that surgery was necessary for physical therapy to work. Evaluation by a specialist surgeon familiar with neglected CMT was recommended. Surgery with unipolar release was performed in November 2020 and according to the surgeon there was a lot of scar tissue that had to be removed. Directly after surgery a neck brace was applied (figure 6), and used day and night, taken off only when training, showering or eating. The day after surgery she started with active exercises of rotation and lateral flexion of the head, and a combination of these motions. PROM was performed by a PT, and the mother had to learn to perform passive exercises at home done three times daily. One week after surgery stretching and exercises were included to find a straight head position. After a couple of weeks, strengthening of the lateral flexors of the opposite side was introduced. A week after surgery she had problems with the brace which irritated her skin, and instead of the brace kinesiology taping with correcting technique was used on the opposite side. With taping, awareness arises when the head tilts away from the applied tape.

Six months after surgery her head had a straight position, there was less facial asymmetry, good motion in her neck bilaterally, and the scolios in her back had improved. The lateral flexors on the opposite side were a little bit stronger, which was our goal with the strength training, and this imbalance will even out in time. She also said spontaneously that she had better self-confidence thanks to the improvement after surgery and rehabilitation. On Cheng and Tang´s scoring system, her scores improved from 0 to 17 after surgery. This is 17 of 21 possible scores, i.e. on the level of excellent. At this time, she had obvious facial asymmetry which is why she did not get a full score in this part. At follow-up in March 2025, four and a half years after surgery, her head is mostly in a straight position with a minor tilt to the left when she gets tired. PROM in rotation 70° bilaterally which is in the normal PROM in neck rotation for adults (37). PROM for lateral flexion was equal on both sides but there was a little tension on the left side when her right ear reached her right shoulder in lateral flexion towards the right side. There was also a minor difference in strength in the lateral flexor, when tested manually she feels that she can push a little more with the left side. To prevent problems in the future, she was given strengthening exercises for lateral flexors on the right side. She still feels that she got a new life after surgery. She mentioned that when she was younger, before surgery, she got a lot of annoying questions about her head position that she is now pleased to be rid of.

Discussion

The described case had severe limited PROM in rotation bilaterally in the neck before surgery. In my experience, most adults with neglected CMT have only limited rotation toward the affected side, normal rotation is usually found on the opposite side. In this case cord tightness on the affected left side was severe and gave an unusually short and very small SCM muscle, probably contributing to limited active and passive ROM in rotation bilaterally. After surgery for unipolar release on the left side and physical therapy, she had equal rotation in her neck bilaterally and still had at her four-and-a-half-year follow-up. PROM in neck rotation decreases as age increases (38, 39, 40, 41). In contrast PROM in lateral flexion of the neck seems to remain almost unchanged (42). Based on the author’s experience, if a young adult lies on their back with their head outside the bench to allow free movement, the evaluator can passively move the head, ear to the shoulder.

For the described case unipolar release gave excellent results. In a study about neglected torticollis in adolescents/adults, Funao et al concluded that unipolar sternocleidomastoid release has benefits over bipolar release. Unipolar release results were just as good as bipolar in their study and were less invasive, minimizing surgical scars and avoiding nerve damage (20). Others find bipolar release to be superior to unipolar (28) or use of other techniques i.e. using z-plasty (32). The imbalance in strength of lateral flexors in the neck usually also persists after surgery, with the affected side stronger. Based on the author’s experience, it is only a few of very young infants that will not have this imbalance, i.e. infants below the age of six to seven months at the time of surgery. Strength training is started three to five weeks after surgery, depending on how the patient manages the exercises. Often the unaffected side needs to gain more strength than the affected side temporarily to achieve a spontaneously relaxed symmetric head position. Muscle strengthening exercises are strongly recommended for children older than four years according to Choi et al (24). Also, younger patients need to be stronger on the opposite side to overcome habitual tilting of the head to the affected side (6). In a clinical setting, you can see that patients have a problem with perception of midline. They feel their head position is tilted to the opposite side when they are straight and when they tilt to the affected side they feel their head position is straight. This is also seen in younger children aged four to five years who can confirm this when asked. For older patients, the tilted position has been the normal for many years and it takes time to relearn. Based on the author’s experience it takes a long time for most adolescents/adults who have tilted their head for several years to get good perception of midline.

Older patients often say they got a new life after surgery, for some also better self-confidence. Adolescents and adult patients with neglected CMT are often very motivated for training, and surgery is often a prerequisite for rehabilitation to work. Gaining good PROM in the neck after surgery is the easier part, getting stronger on the unaffected side and especially reestablishing perception of midline can demand considerable effort from the adolescent/adult. Some who have surgery in childhood need more surgery years later (21). The SCM muscle grows from 4 cm in infanthood to 14 cm at 13 years of age (43). If there is any fibrosis left in the muscle this may cause recurrent problems. For the adolescent/adult with neglected CMT, it is not uncommon for them to have had many unsuccessful visits before they meet a professional who understands the need for surgery. During the years the author has met about 30 patients ranging from 16 to 30 years old who have had a history of neglected CMT and needed surgery. Several of the patients had met different professionals: physicians, physiotherapists, naprapaths, chiropractors etc. who lacked enough knowledge of CMT and surgery. These patients were told that nothing could be done, two of them who got botulinum injections, which according to them only resulted in pain. Adolescents/adults with neglected CMT are generally resistant to any non-surgical treatments (20). Funao et al found in their series no cases of success with botulinum injections (20). One of the author’s patients was a young 28-year-old man who had met a lot of different professionals during a period of seven years and not one suggested surgery. He could explain his condition so well on the telephone that it was obvious he needed surgery even before we met. Earlier he had been given stretching exercises and botulinum injections without any positive effect – they only resulted in pain. A couple of weeks after surgery the case was very pleased and spontaneously said “This is like having a new life.” During the years I have heard the same from several adult patients in the same situation. Improved quality of life after surgery for neglected CMT can be seen in several studies (28, 35). Høiness et al found significant improvement both in health-related quality of life (HRQoL) and clinical outcomes in children, adolescents and young adults who underwent surgical release for neglected CMT (35).

Conclusion

There is a lack of knowledge about severe cases of CMT in the health care system resulting in neglected CMT that causes problems for the individual. Surgery can be of great benefit to an adolescent/adult. More awareness among health care professionals is required to find those in need of surgery in an optimal time and to avoid unnecessary suffering. Guidelines for surgery for all ages and for neglected CMT are needed.

Funding: This case report received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement: Ethical review and approval were waived for this study, due to Swedish Ethical Review Authority Statement: “If the intended publication contains only accounts of diagnosis and treatment, or of some other course of events, this practice should be understood not to be a matter of research that must be ethically tested” (https://etikprovningsmyndigheten.se/faq/kravs-etikprovning-for-fallrapporter/).

Informed Consent Statement: Informed consent was obtained from the case to use photos.

Conflicts of Interest: The author declares no conflicts of interest.

References

- Stellwagen L, Hubbard E, Chambers C, Lyons Jones K. Torticollis, facial asymmetry and plagiocephaly in normal newborns. Arch Dis Child 93 (2008): 827-831

- Cheng JCY, Wong MWN, Tang SP, Chen TM, et al. Clinical determinants of the outcome of manual stretching in the treatment of congenital muscular torticollis in infants. J Bone Joint Surg Am 83 (2001): 679-687.

- Emery C. The determinants of treatment duration for congenital muscular torticollis. Phys Ther 74 (1994): 921-928.

- Cheng JCY, Au AWY. Infantile torticollis: A review of 624 cases. Journal of Pediatric Orthopaedics 14 (1994): 802–808.

- Golden KA, Beals SP, Littlefield TR, and et al, Sternocleidomastoid imbalance versus congenital muscular torticollis: their relationship to positional plagiocephaly: Cleft Palate-Craniofacial J 36 (1999): 256-261.

- Öhman A, Mårdbrink E-L, Stensby J, Beckung E. Evaluation of treatment strategies for muscle function in infants with congenital muscular torticollis. Physiotherapy Theory Practice 27 (2011): 463-470.

- Öhman A, Beckung E. Reference values for range of motion and muscle function in the neck—in infants. Pediatr Phys Ther 20 (2008): 53-58.

- Cheng JCY, Tang SP. Outcome of surgical treatment of congenital muscular torticollis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 362 (1999): 190-200.

- Lee EH, Kang YK, Bose K. Surgical correction of muscular torticollis in the older child. J Pediatr Orthop 6 (1986): 585-589.

- Itio E, Funayama K, Suzuki T, Kamio K, et al. Tenotomy and postoperative brace treatment for muscular torticollis. Contemp Orthop 20 (1990): 515-523.

- Minamitani K, Inoue A, Okuno T. Result of surgical treatment of muscular torticollis for patients 6 years of age. J Pediatr Orthop 10 (1990): 754-759.

- Strassen LFA and Kerawala CJ. New surgical technique for the correction of congenital muscular torticollis (wry neck). British Journal of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery 38 (2000): 142–147.

- Baratta VM, Linden OE, Byrne ME, Sullivan SR and Taylor HO. A quantitative analysis of facial asymmetry in torticollis using 3-dimensional photogrammetry. The Cleft Palate-Craniofac J 59 (2022): 40-46.

- Burstein FD and Cohen SR. Endoscopic surgical treatment for congenital muscular torticollis. Plast Reconstr Surg 110 (1998): 20.

- Greenberg MF, Pollard ZF. Ocular plagiocephaly: Ocular torticollis with skull and facial asymmetry. Ophthalmology 107 (2000): 173-178.

- Castro MP, Rey RL, Mahia IV and Lopez-Cedrun JL. 2014 Congenital muscular torticollis in adult. Patients: Literature review and a case report using a harmonic scalpel. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 72 (2014): 396-401.

- Kittur D. The fate of facial asymmetry after surgery for muscular torticollis in early childhood. J Indian Assoc Pediatr Surg 21 (2016): 57-60.

- Beek DM, avn Vlimmeren L, BrugginkR, Pelsma M, et al. The effect of combined surgery and physiotherapy on facial asymmetry in patients with congenital muscular torticollis: a retrospective cohort study. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 53 (2024): 919-924.

- Ippolito and Tudisco. Idiopathic muscular torticollis in adults. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 105 (1986): 4954.

- Funao H, IsogaiN, Otomo N, et al. Clinical results after release of sternocleidomastoid muscle surgery for neglected congenital torticollis-Unipolar vs. Bipolar release surgery. J Clin Med 13 (2023): 131.

- Moussaoui A, Ennouhi MA and Guerrouani A. A rare case of neglected congenital muscular torticollis in adult and review of literature. BJMMR 7 (2015): 541-549.

- Khoury J. Is Sternocleidomastoid muscle release effective in adults with neglected congenital muscular torticollis? Clin Orthop Relat Res 472 (2014): 1271-1278.

- Omidi-Kashani F, Hasankhani EG, Sharifi R and et al. Is surgery recommended in adults with neglected congenital muscular torticollis? A prospective study. BMC Musculoskeletal Disorders 26 (2008): 9:158.

- Choi JM, Seol SH, Kim JH, et al. CORR Insights: Age group-specific improvement of vertebral scoliosis after the surgical release of congenital muscular torticollis. Arch Plast Surg 51 (2024): 72-9.

- Kim HJ, Ahn HS and Yim S-Y. Effectiveness of surgical treatment for neglected congenital muscular torticollis: A systematic review and Meta-analysis. Plast Reconstr Surg 136 (2015): 67e-77e.

- Piza-Katzer H. Surgical revision of congenital muscular torticollis in an adult male with established facial asymmetry. Eur Surg 39 (2007): 61-66

- Hyun JK, Hyeong SA and Yim S-Y. Effectiveness of surgical treatment for neglected congenital muscular torticollis: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Plast. Reconstr. Surg 136 (2015): 67e-77e.

- Lee GS, Lee MK, Kim WJ, et al. Adult patients with congenital muscular torticollis treated with bipolar release: Report of 31 cases. J Korean Neurosurgical Society 60 (2017): 82-88.

- Kim J-H, Yum T-H and Shim JS. Secondary cervicothoracic scoliosis in congenital muscular torticollis. Clin Orthop Surg 11 (2019): 344-351.

- Min K-J, Ahn a-R, Park E-J and Yim S-Y. Effectiveness of surgical release inpatients with neglected congenital muscular torticollis according to age at time of surgery. Ann Rehabil Med 40 (2016): 34-42.

- Öhman AM, Perbeck Klackenberg EB, Beckung ERE, et al. Functional and cosmetic status after surgery in congenital muscular torticollis. Advances in Physiotherapy 8 (2006): 182–187.

- Kaplan SL, Coulter C and Fetters L. Physical therapy management of congenital muscular torticollis: an evidence-based clinical practice guideline: from the section on pediatrics of the American physical therapy association. Pediatr Phys Ther 25 (2013): 348-394.

- Kaplan SL, Coulter C and Sargent B. Physical therapy management of congenital muscular torticollis: a 2018 evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the APTA Academy of pediatric physical therapy. Pediatr Phys Ther 30 (2018): 240-290.

- Sargent B, Coulter C, Cannoy J and Kaplan SL. Physical Therapy management of congenital muscular torticollis: A 2024 evidence-based clinical practice guideline from the American physical therapy association academy of pediatric physical therapy. Ped Phys Ther 36 (2024): 370-421.

- Høiness PR and Medbø A. Surgical treatment of congenital muscular torticollis: Significant improvement in health-related quality of life among a 2-year follow-up cohort of children, adloescents and young adults. J Pediatr Orthop 43 (2023): e769-e774.

- Oldzka M and Shur M. Postsurgical physical therapy management of congenital muscular torticollis. Pediatr Phys Ther 29 (2017): 159-165.

- Apti A, Colak TK and Akcay B. Normative values for cervical and lumbar range of motion in healthy young adults. J Turk Spinal Surg 34 (2023): 113-117.

- Feipel, Rondelet, Pallec, and Rooze. Normal global motion of the cervical spine: an electrogoniometric study. Clin Biomech (Bristol) 14 (1999): 462-470.

- Lynch-Caris, Majeske, Brelin- Fornari, and Nashi. Establishing reference values for cervical spine range of motion in pre-pubescent children. J Biomech 28 (2008): 2714-2719.

- Seacrist T, Saffioti J, Balasubramanian S, et al. Passive cervical spine flexion: The effect of age and gender. Clin Biomech (Bristol) 27 (2012): 326-33.

- Youdas, JW, Garrett TR, Suman VJ, et al. Normal range of motion of the cervical spine: An initial goniometric study. Physical Therapy 72 (1992): 770-780.

- Öhman A, beckung E. A pilot study on changes in passive range of motion in the cervical spine, for children aged 0-5 years. Physiother Theory Pract 29 (2012): 457-460.

- Jones PG. Torticollis in infancy and childhood. Springfield, IL Charles C Thomas (1968): 107-108.