Exploring Telemedicine in Rural Hospitals in Taiwan: A Study on Key Success Factors Based on the DEMATEL Method

Kuo-Fang Hsu1, Ping-Lung Huang*,2, Bruce C.Y. Lee3, Cheng-Ta Yeh4

1Ph. D & Director, Miaoli Hospital, Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan

2Assist Professor, Bachelor's Program in Business Management, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan

3Professor, Department of Finance and International Business, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan

4Professor, Bachelor's Program in Business Management, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan

*Corresponding author: Ping-Lung Huang, Assist Professor, Bachelor's Program in Business Management, Fu Jen Catholic University, Taiwan.

Received: 05 June 2025; Accepted: 12 June 2025; Published: 07 July 2025

Article Information

Citation: Kuo-Fang Hsu, Ping-Lung Huang, Bruce C.Y. Lee, Cheng-Ta Yeh. Exploring Telemedicine in Rural Hospitals in Taiwan: A Study on Key Success Factors Based on the DEMATEL Method. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences. 8 (2025): 618 - 631.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Since the establishment of Taiwan's National Health Insurance (NHI) program in 1995, urban regions have achieved remarkable healthcare outcomes. However, remote and island areas continue to face obstacles in accessing medical services due to transportation challenges and resource constraints. In response, the Taiwan government-initiated telemedicine advancements in 2019, demonstrating significant benefits, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic. This study analyzes a telemedicine outpatient program at a rural hospital in southern Taiwan using the Decision-Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) method. The aim is to identify critical factors contributing to the program's success. Findings highlight the importance of supplier collaboration and robust technical capabilities, coupled with comprehensive education and training plans. Addressing risks and balancing key factors are vital to achieving sustainable outcomes. This study provides valuable insights for rural healthcare institutions, supporting the optimization of telemedicine and fostering equitable healthcare access and improved public health.

Keywords

Policies, Telemedicine, Healthcare, DEMATEL, Key Success Factors

Policies articles, Telemedicine articles, Healthcare articles, DEMATEL articles, Key Success Factors articles

Article Details

Introduction

Health is a fundamental human right and a universal value in society. The preamble of the World Health Organization (WHO) Constitution states that the highest attainable standard of health is a basic right for all individuals, regardless of race, religion, political beliefs, social, or economic conditions (WHO, 1946). One of the key sustainable development goals set by the WHO for 2030 is Universal Health Coverage (UHC), which aims to ensure that all individuals have access to high-quality, continuous healthcare services throughout their lives without facing financial hardship (WHO-OECD-World Bank, 2018a; WHO, 2016a). However, for residents living in remote areas, healthcare accessibility has long been a major challenge. Despite their medical needs, geographical barriers prevent them from accessing nearby healthcare facilities, often necessitating referrals to distant hospitals, thereby increasing the cost and difficulty of seeking medical care. Healthcare should not be a privilege determined by economic or geographical factors. Therefore, this study explores the critical success factors of telemedicine outpatient services, their potential benefits in integrating medical resources in rural areas, and their implications for future policy development. The findings will provide healthcare administrators with guidance on optimizing resource allocation within constrained environments to enhance competitiveness and service effectiveness. To achieve universal health coverage and ensure that residents in remote areas receive high-quality and comprehensive medical services, Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare promulgated the Regulations on Telemedicine Diagnosis and Treatment on May 11, 2018. This policy aims to supplement the medical capacity in underserved areas through telemedicine consultations and treatments. By establishing telemedicine outpatient services, the government seeks to enhance healthcare accessibility in remote areas, improve service quality, and facilitate localized medical care, allowing patients to receive treatment without the need for physical displacement. The goal is to integrate specialized medical personnel, strengthen healthcare capacity in remote regions, and provide essential but non-emergency medical consultations that meet local residents' needs. Furthermore, the policy promotes the establishment of community-friendly healthcare institutions, enabling residents to access specialist consultations without incurring excessive travel time and prolonged waiting periods. As Buck (2009) noted, telemedicine can offer continuous and convenient healthcare services, reducing both the distance and time required for medical consultations.

Literature Review

Current Situation of Healthcare in Rural Areas of Taiwan

Healthcare institutions in Taiwan’s rural and offshore areas have long faced challenges due to inconvenient transportation, sparse and scattered populations, and limited economic scale. These factors make it difficult to recruit medical professionals, resulting in disparities in healthcare resources and quality compared to urban areas. To improve healthcare quality and enhance local medical capacity, government intervention through relevant policies is necessary. The following section explores the common challenges currently faced by rural healthcare in Taiwan. According to data released by the Taiwan’s Ministry of Health and Welfare in 2020, large-scale medical institutions in Taiwan are predominantly concentrated in metropolitan areas in the northern and western regions, whereas the eastern regions and offshore islands suffer from a severe shortage of healthcare facilities. Huang Hui-Wen (2020) analyzed the proportion of healthcare institutions in rural areas in relation to the total number of medical facilities nationwide, categorized by hospital levels. For a detailed breakdown, refer to Table 1, which illustrates the proportion of rural hospitals among all healthcare institutions in Taiwan.

Table 1: Proportion of Rural Hospitals in Taiwan’s Healthcare System

|

Category |

Indigenous Areas |

Offshore Islands |

Highly Remote Areas |

Subtotal |

|

Medical Centers |

1 |

0 |

0 |

1 |

|

Regional Hospitals |

3 |

0 |

0 |

3 |

|

District Hospitals |

8 |

4 |

8 |

20 |

|

Clinics |

337 |

97 |

264 |

698 |

|

Total |

349 |

101 |

272 |

722 |

|

Proportion of Total Healthcare Institutions in Taiwan |

2.93% |

0.85% |

2.26% |

6.04% |

Source: Huang Hui-Wen (2020).

From the statistics above, it is evident that healthcare capacity in rural areas is significantly inadequate. Only the indigenous areas have a medical center and regional hospitals, with one and three respectively. The majority are clinics, but these clinics typically have a limited range of specialties, and their manpower and equipment are insufficient to provide appropriate care for critically ill patients in a timely manner. In offshore islands, the highest level of hospitals available is only district-level hospitals, making them particularly vulnerable in terms of healthcare access. Overall, healthcare institutions in indigenous areas, offshore islands, and highly remote areas together account for only 6.04% of the total healthcare institutions in Taiwan, a proportion that is considerably low.

Definition of Telemedicine

Telemedicine, also known as telehealth, refers to the use of digital information and communication systems to overcome the limitations of time and space, enabling interactive medical consultations and advisory services. In 2007, the World Health Organization (WHO) provided a standardized definition of telemedicine: "The use of information and communication technology by healthcare professionals to exchange diagnostic information, effective treatment information, as well as for the prevention of diseases and injuries, research, evaluation, and continuing education through interactive video for healthcare providers, all for the purpose of promoting the health of individuals and communities and delivering healthcare services." Today, telemedicine combines computers, network communications, and related medical equipment, allowing clinicians to conduct remote meetings and virtual consultations, thereby eliminating the geographical barriers of healthcare. In general, telemedicine integrates various forms of data such as text (e.g., medical records, examination reports), numbers (e.g., test results), images (e.g., CT scans, MRIs, X-rays), video (e.g., endoscopies, angiographies), and audio to transmit patient medical information. This allows consulting physicians at collaborating medical centers to receive timely information, make diagnoses, and provide appropriate treatment, thereby ensuring that people in remote areas no longer need to travel long distances.

According to the WHO’s definition of telemedicine, it should include the following four key elements (WHO, 2010):

- The purpose is to provide clinical support.

- It exists to overcome geographical barriers across different regions.

- It operates through various forms of information and communication technology.

- The goal is to improve health outcomes.

Currently, telemedicine is seen as a solution to healthcare issues in areas with limited resources and shortages of medical personnel, particularly in remote regions (Miller et al., 2003). With advancements in technology, the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic, and the relaxation of related regulations and policies, telemedicine has gained increasing attention from the public. Furthermore, with advancements in communication technology, telemedicine is a healthcare model that bridges time and space constraints while consolidating physicians' expertise into a collaborative, interactive healthcare approach (Zhang et al., 2021). Unlike traditional face-to-face medical services, telemedicine can create more added value in healthcare, providing greater assistance in achieving universal health coverage in the near future.

Forms of Telemedicine

Telemedicine can be categorized into three main forms based on the target audience:

(1) Clinical Physician to Clinical Physician:

Physicians use information and communication technology to conduct specialist consultations. Specialists from medical centers provide diagnostic and treatment support to clinics or hospitals in remote areas, such as dermatology, ophthalmology, otolaryngology, and emergency care, thus reducing the need for patients to travel long distances. This consultation method has been widely adopted, and this study focuses on the benefits of telemedicine for rural hospitals.

(2) Clinical Physician to Patient:

Physicians use information and communication technology to provide medical treatment to patients, which is the most familiar form of telemedicine.

(3) Patient to Digital Mobile Device:

Patients use digital mobile devices to collect symptoms and physiological information, which are then analyzed by a telecare platform that provides alerts for abnormal values and educational feedback.

Therefore, telemedicine can be broadly divided into several categories, such as Tele-diagnostics, Teleconsultation, Tele-treatment, Tele-care, and Health telematics (Deldar et al., 2016).

According to Hong Qi-Sheng (2021), the development of telemedicine can be categorized into four generations based on three criteria: data transmission forms, the level of integration with patient healthcare systems, and decision-making capabilities:

(1) First Generation Telemedicine System:

This system involves non-responsive data collection, where physiological or clinical information is collected but caregivers do not provide immediate responses, and data transmission is not synchronized.

(2) Second Generation Telemedicine System:

This system provides non-real-time telecare, where data is uploaded by patients, but caregivers cannot provide immediate feedback or judgment.

(3) Third Generation Telemedicine System:

This system is a telecare management system, where caregivers respond and make judgments immediately upon receiving data uploaded by the patient.

(4) Fourth Generation Telemedicine System:

This system is a complete telecare system that integrates patient medical records in addition to the features of the previous generations, allowing caregivers to make personalized decisions in real time.

The development of telemedicine can be traced back several decades. However, in recent years, with advancements in information and communication technology, the widespread use of smartphones, and high-speed internet, telemedicine has made significant breakthroughs. These advancements have removed the constraints of time and space, allowing residents in remote areas to access the personalized, continuous healthcare services they need, closer to home.

Key Success Factors (KSF)

The concept of Key Success Factors (KSF) was first introduced by organizational economist Commons (1934), who referred to them as "limited factors" and applied them in management and negotiations. Later, Barnard (1948) incorporated this idea into decision-making theory, suggesting that the analytical work of decision-making is essentially the process of identifying "strategic factors." Daniel (1961) further explored KSF from the perspective of Management Information Systems (MIS), explaining the role of key success factors. KSF was first applied in non-executive information systems by Drucker (1964), who used it in organizational design. Steiner (1969) applied the perspective of strategic factors in strategic analysis. The term "key success factors" was co-introduced by Hofer and Schendel (1977). In early research on KSF, different terms were used, such as limited factors, strategic factors, key variables, or strategic variables. However, after 1978, an increasing number of scholars entered this field, and the terminology and perspectives began to align. According to Boynton & Zmud (1984), the function of KSF is beneficial in the planning of resource demands and information systems. KSF serves as a bridge for communication between program managers and designers, reducing cognitive gaps and aligning with the needs of information management systems and resource demand planning.

The key functions of KSF include:

- Guiding the allocation of organizational resources.

- Simplifying operations for management hierarchies.

- Detecting business performance.

- Communicating and planning management information systems.

- Analyzing the strengths and weaknesses of competitors.

Pollalis & Frieze (1993) identified three main functions of KSF:

- Efficient planning.

- Facilitating communication.

- Control over processes.

Identifying Key Success Factors:

Rockart (1979) outlined a process for identifying KSFs that align with the organization's overall goals:

- Identify general success factors:

Ask the organization's CEO about the factors they believe contribute to the company's success. This step yields a series of general success factors.

- Refine success factors to align with overall goals:

Narrow down the success factors to 6-10 critical factors that determine success.

- Establish performance measurement indicators:

Identify the key performance indicators (KPIs) to assess whether the organization has achieved success based on the identified KSFs.

Methodology

Methodology choice

- Through a comprehensive review of relevant literature, eleven critical evaluation factors for the success of telemedicine were identified and synthesized. These factors include the stability and accuracy support of hospital information systems, the information literacy of hospital (medical) personnel, the technical capability and cooperation of hospital suppliers, personal data security management, the ease of operation of medical equipment interfaces, the support and professional competence of medical personnel, the full support of hospital management, the cooperation of administrative staff, the planning and execution of training programs, clear policies and regulations, and the referral and follow-up medical support system (Table 2), and Operational Definition (Table 3). Based on these factors, a DEMATEL questionnaire on the key success factors of telemedicine was developed (Table 3).

- After the DEMATEL questionnaire on the key success factors of telemedicine was finalized, it was distributed or sent to relevant personnel involved in telemedicine outpatient services in rural hospitals, including outpatient physicians, nurses, unit supervisors, and personnel from management centers. The questionnaire was also distributed to business representatives, relevant physicians, and nurses from medical centers that provide support and consultation services for telemedicine outpatient clinics. Additionally, it was sent to officials responsible for telemedicine affairs at central government agencies, hospital executives who have participated in telemedicine programs, senior officials from local health authorities, and frontline personnel from other rural hospitals with experience in implementing similar telemedicine projects.

Table 2. Summary of Key Success Factors in Telemedicine

|

Evaluation Factors (Dimensions) |

Relevant Literature |

|

(a) Stability and Accuracy Support of Hospital Information Systems |

Broens et al. (2007), |

|

Cilliers (2010), |

|

|

Judik et al. (2009), |

|

|

Kodukula and Nazvia (2011), |

|

|

Wade et al.( 2014) |

|

|

(b) Information Literacy of Hospital (Medical) Personnel |

Judik et al. (2009), |

|

Cilliers (2010), |

|

|

Liu (2011), |

|

|

Wade et al. (2014) |

|

|

(c) Technical Capability and Cooperation of Hospital Suppliers |

Broens et al. (2007), |

|

Cheng & Shih (2006), |

|

|

Cheng Yung-Ming & Shih Po-Chou (2006), |

|

|

Liu (2011) |

|

|

(d) Personal Data Security Management |

Haas and Sembritzki (2006), |

|

Broens et al. (2007), |

|

|

Cilliers (2010), |

|

|

Judik et al. (2009) , |

|

|

Hossein Ahmadi (2014) |

|

|

(e) Ease of Use of Medical Equipment Interfaces |

Haas and Sembritzki (2006) , |

|

Broens et al. (2007) , |

|

|

Buck (2009), Cilliers (2010), |

|

|

Hossein Ahmadi (2014), |

|

|

Wade et al. (2014) |

|

|

(f) Support and Professional Competence of Medical Personnel |

Broens et al. (2007), |

|

Cilliers (2010), |

|

|

Buck (2009) |

|

|

(g) Adequate Support from Hospital Management |

Haas and Sembritzki (2006), |

|

Cilliers (2010), |

|

|

Cook et al. (2001) |

|

|

Judik et al. (2009), |

|

|

West et al. (2011) |

|

|

(h) Cooperation of Administrative Staff |

West et al. (2011), |

|

Cilliers (2010) |

|

|

Cook et al. (2001) |

|

|

(i) Planning and Implementation of Training Programs |

Broens et al. (2007), |

|

Buck (2009), |

|

|

Cilliers (2010), |

|

|

Judik et al. (2009), |

|

|

Hossein Ahmadi (2014), |

|

|

Kodukula and Nazvia (2011), |

|

|

West et al. (2011), |

|

|

(j) Clear Policies and Regulations |

Broens et al. (2007), |

|

Cilliers (2010), |

|

|

Judik et al. (2009), |

|

|

Kodukula and Nazvia ( 2011) |

|

|

(k) Referral and Follow-up Medical Support Mechanisms |

Broens, Vollenbroek-Hutten et al.( 2007), |

|

Kodukula and Nazvia (2011), Liu( 2011) |

Source: Literature Review and This Study

Table 3: Table Definition of Research Variables

|

Evaluation Factors |

Description |

|

(a) Stability and Accuracy of Hospital Information System Support |

Whether the hospital's information system is stable and accurate in response to telemedicine? |

|

(b) Information Competence of Hospital (Medical) Staff |

Whether the medical staff have the information operation competence in response to telemedicine? |

|

(c) Technical Capability and Cooperation of Hospital Suppliers |

Whether the hospital's suppliers have the technical capability and cooperation in response to telemedicine? |

|

(d) Personal Data Security Management |

How the security management of patients' personal data is handled in response to telemedicine? |

|

(e) Ease of Operation of Equipment Interfaces |

Whether the equipment or device has ease of operation in response to telemedicine? |

|

(f) Support and Professional Capability of Medical Staff |

Whether the medical staff have sufficient support and professional capability in response to telemedicine? |

|

(g) Adequate Support from Hospital Management |

Whether the hospital management provides sufficient support in response to telemedicine? |

|

(h) Cooperation of Support (Administrative) Staff |

Whether the hospital support (administrative) staff cooperate sufficiently in response to telemedicine? |

|

(i) Planning and Implementation of Education and Training |

How the hospital plans and implements education and training for relevant personnel in response to telemedicine? |

|

(j) Clear Policies and Laws |

Whether there are clear policies and laws in response to telemedicine? |

|

(k) Referral and Follow-up Medical Support Mechanisms |

Whether there are referral and follow-up medical support mechanisms in response to telemedicine? |

Source: Literature review and this study's organization

DEMATEL method

- Questionnaire design

The second questionnaire designed for DEMATEL (Tzeng et al., 2007). This questionnaire designed for pairwise comparison to evaluate the influence of each score, where scores of 0, 1, 2, and 3 represent: (no influence), (low influence), (high influence), and (very high influence), respectively (Tamura and Akazawa, 2005). (Show on Table 4)

Table 4: The DEMATEL questionnaire of the key success factors for telemedicine outpatient clinics of Taiwanese in Rural Area

Score: 0: no influence 1: low influence 2: high influence 3: very high influence

2 Analyses process:

Step 1: acquire and compute the average initial matrix

Suppose L experts and n factors are considered in a study. A pair-wise comparison with respect to the influence of factor on factor j is determined and is quantified using a 4-point (0–3) measurement scale. See Table 4 for the linguistic assignments of each level of the scale. Each expert will be asked to provide a completed non-negative response matrix , with . Where represents each of the experts response matrices, is an integer (scale measure) representing each element of and diagonal elements of each response matrix set to zero. An averaged matrix using all the experts’ comparisons is determined by averaging the experts’ scores using expression (1)

Step 4 Drawing the Causal diagram

The and are respectively the sums of rows, and columns from the total-relation matrix , then calculate the degree of effect (D+R) and the degree of cause (D-R), where (D+R) represents the strength of the relationship between the criteria, and (D-R) represents the strength of the criterion's influence or impact.

There are (D+R) and (D-R) values of each criterion are plotted on the graph, with (D+R) as the horizontal axis; (D-R) as the vertical axis. (Show on Figure 1).

Sampling

To more effectively analyze the critical success factors of telemedicine outpatient services in rural areas, the "Expert Questionnaire" targets individuals involved in telemedicine at a rural hospital in Pingtung, Taiwan. This includes relevant medical personnel, hospital managers, and health authority officials. The goal is to use the Decision Making Trial and Evaluation Laboratory (DEMATEL) method to analyze the expert questionnaire and identify genuinely meaningful critical success factors. The expert questionnaire is compiled from literature and is representative.

Research Results

Sample Structure Analysis

According to the categories of hospital sources, there were a total of 20 questionnaires from district hospitals, accounting for 64.5%, including three regions: Hua-Lien, Tai-Tung, and Heng-Chun. Among similar-sized rural hospitals, 5 questionnaires were recovered from regional hospitals, accounting for 16.1%, and 6 questionnaires from medical centers, about 16.4%. From the questionnaire responses, the higher response rate mainly came from healthcare-related personnel at rural district hospitals and medical centers, with the medical center representatives primarily from a certain medical center in Kaohsiung.(show on Table 5).

Table 5: Sample Structure Analysis Table

N=31

|

Item |

Number of Responses |

Response Rate |

Cumulative Response Rate |

|

Gender |

|||

|

Male |

17 |

55% |

55% |

|

Female |

14 |

45% |

100% |

|

Employment Tenure |

|||

|

Less than 5 years |

7 |

23% |

23% |

|

6-10 years |

5 |

16% |

39% |

|

11-15 years |

4 |

13% |

52% |

|

16-20 years |

5 |

16% |

68% |

|

More than 21 years |

10 |

32% |

100% |

|

Position |

|||

|

Doctor |

9 |

29.00% |

29.00% |

|

Nurse |

12 |

38.70% |

67.70% |

|

Administrative Staffs |

6 |

19.40% |

87.10% |

|

Other Personnel (Authorities) |

4 |

12.90% |

100.00% |

|

Hospital Source |

|||

|

District Hospital |

20 |

64.50% |

64.50% |

|

Regional Hospital |

5 |

16.10% |

80.60% |

|

Medical Center |

6 |

19.40% |

100.00% |

Source: Compiled from Questionnaire Data

DEMANTEL analysis results

DEMANTEL analysis process

As follows DEMANTEL analyses process and found result below:

Step 1: Based on the questionnaire survey results, calculate the average initial matrix A (N = 31; see Table 6).

Table 6: Overall average expert opinion matrix (matrix A)

Data Source: Compiled from this study

Step 2: Compute the normalized initial direct-relation matrix D, show on table 7.

Table 7: Normalized direct relation matrix (matrix D)

Data Source: Compiled from this study

Step 3: Compute the total relation matrix T, show on table 8.

Table 8: Total impact matrix (matrix T)

Data Source: Compiled from this study

Step 4: Drawing the Causal diagram

- Analyzing the degree of central role and relation:

As get the analyzed result the matrix T (Show on table 8), then we can calculate the degree of central role (Dx + Rx) and (Dx - Rx) values. The degree of central role (Dx + Rx) and (Dx - Rx) in DEMATEL represents the strength of influences both dispatched and received. On the other hand, if the (Dx - Rx) is positive, then the evaluation criterion x dispatches the influence to other evaluation criteria more than it receives. If the (Dx - Rx) is negative, the evaluation criterion x receives the influence from other evaluation criteria more than it dispatched. The (Dx - Rx) values are reported in Table 9.

Table 9: The degree of central role (D+R) sheet

Data Source: Compiled from this study

- Drawing causal diagram

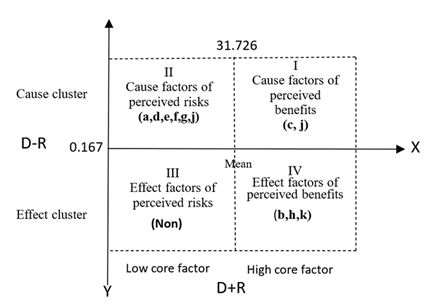

The next step is to plot various criteria on two (X/Y) axes, highlighting the horizontal axis's degree of connectivity (D+R) and the vertical axis's degree of causality (D–R). Following the results shown in Table 9, draw the cause-effect diagram as shown in Figure 2, which represents the form and graphical relationships. This makes the structure and relationships of the criteria clearer.

Discussion

The application of new technologies directly affects interpersonal interactions. While telemedicine can provide medical services to rural areas, it may also lead to the so-called "island effect" (Chen, 2011). In healthcare, communication through video media can sometimes feel impersonal compared to traditional face-to-face interactions. Patients may find it hard to fully trust machines and video communication, and this mistrust is especially pronounced among the elderly, which can affect the establishment and maintenance of doctor-patient relationships (Tsai, 2000). To address the challenges faced by rural areas in Taiwan regarding medical resources, comprehensive efforts are needed to improve the health standards of local residents. The feasibility and limitations of "telemedicine" in rural areas require thorough exploration. Modern technological developments and supportive regulations must be applied to address the lack of medical resources in rural areas. Regarding the two core factors of "the alignment of hospital suppliers' technical capabilities" and "the planning and implementation of education and training," we can explore their significant implications from both academic and managerial perspectives:

- (c) The alignment of hospital suppliers' technical capabilities: Academically, this involves telemedicine equipment and digital communication technologies. The ability of suppliers to provide highly stable, compatible, and user-friendly technical support directly impacts the successful implementation of technology. This serves as a basis for studying the Technology Acceptance Model (TAM), the Diffusion of Innovation theory, and organizational internal technology integration. From a managerial perspective, ensuring the stability and adaptability of technology, and integrating it with existing medical systems, is crucial. Excellent technical suppliers should establish deep cooperative relationships with medical institutions, provide timely technical support, and enhance service quality. Managers need to develop preventive strategies to address potential technical defects and service delays to ensure the successful operation of remote consultations.

- (i) The planning and implementation of education and training: Academically, enhancing the operational capabilities of medical and managerial personnel in telemedicine is key. This involves the application of knowledge management in medical contexts. Education and training can improve digital literacy and trust, influencing attitudes and behaviors, which is closely related to behavior change models. Investigating whether practical training and case study-based teaching are more effective in internalizing knowledge and enhancing application capabilities is a research direction.

Through these comprehensive efforts, we can gradually improve the medical resource challenges in rural areas and enhance the health levels of local residents. Overall, the academic and managerial implications of these two core factors complement each other, reflecting the core challenges and opportunities in promoting remote consultations in rural areas. Designing an Efficient Technological Infrastructure: One challenge is to design a technological foundation that operates efficiently while enabling relevant personnel to learn, adapt to, and effectively apply new technologies. This provides abundant interdisciplinary research material for this academic field. Practice-Oriented Decision-Making Services: Healthcare institutions need to balance technological choices, educational planning, and resource allocation. These management decisions directly affect the success of remote consultations and serve as important references for future similar projects. In other words, these two key factors play crucial roles in the holistic operation of the "Technology-People-Management" system, possessing profound academic research value and practical application significance. The successful implementation of remote medical consultations in rural areas is the result of the interaction of multiple factors, requiring comprehensive cooperation in technology, policy, medical resources, and local society and culture. It also involves continuous monitoring and evaluation of remote medical services, regularly reviewing their effectiveness and shortcomings, and timely adjusting service plans to meet the changing health needs of rural areas. In summary, remote medical consultations in rural areas are not merely the application of technological innovations, but rather a comprehensive action requiring policy support, technological assistance, resource investment, and cultural integration. Only through close collaboration and context-specific advancement can the goal of equal access to health resources be truly achieved, enhancing the well-being of rural residents and fulfilling the objective of medical equity.

Conclusion

The primary aim of this study is to identify potential key success factors for telemedicine and provide them to managers, enabling more effective resource allocation under limited resources to enhance competitiveness. Based on the analysis results shown in Figure 2, the conclusions are as follows:

Quadrant I: Cause factors of perceived benefits:

Factors located in this area have high connectivity and high causality, making them critical key influencing factors for addressing the research topic. These should be prioritized for handling, and management resources should focus on this area. According to the findings of this study, the key influencing factors in Quadrant 1 are: c. Technical capability and cooperation of hospital suppliers and, i. Planning and execution of training programs. Below is a discussion of why these two factors are in the most important core factor area:

- Technical capability and cooperation of hospital suppliers: The promotion of telemedicine outpatient services requires close cooperation between suppliers and hospitals, and the suppliers' level of cooperation determines the efficiency of problem-solving. During actual implementation, there are always demands for system optimization, customization, or unexpected issues. If suppliers are highly cooperative, they can quickly respond to the hospital's needs, provide timely technical support and follow-up services, which helps reduce system downtime, improve medical efficiency, and increase patient satisfaction. When hospitals need suppliers to adjust telemedicine equipment for rural network environments, rapid solutions can ensure uninterrupted services and meet the special medical needs of rural areas. Moreover, the medical environment and basic needs in rural areas differ significantly from urban areas, including inadequate network infrastructure and limited equipment resources. Therefore, suppliers must have the capability to design flexibly and provide customized technical solutions. For example, developing video compression technology for low-bandwidth areas, using lower-cost hardware (such as mobile medical devices), or introducing scalable modular solutions. If suppliers lack such technical innovation and customization capabilities, it will be difficult to effectively address the unique needs and problems of rural areas, hindering the progress of medical service promotion. Forward-thinking suppliers will further develop more smart medical options (such as remote diagnostic aids, AI analysis tools, etc.) after successfully promoting telemedicine outpatient services in rural areas, continuously adding value to medical services.

- Planning and execution of training programs: According to related studies by Bashshur et al. (2011), Wootton and Craig (2016), and Dorsey et al. (2016), education and training for personnel in the field of telemedicine are critical. The development of telemedicine allows medical services to transcend geographical limitations and offer more comprehensive healthcare services. However, the unique nature of telemedicine requires practitioners to possess specific skills and knowledge to ensure the quality and safety of medical services. Among the key success factors for promoting telemedicine outpatient services in rural areas, the planning and execution of education and training for relevant personnel are of utmost importance. As a new medical model, telemedicine necessitates adaptation in technology, processes, collaboration, and culture, and education and training directly affect its effective operation and outcomes.

Quadrant II: Cause factors of perceived risk:

Factors in this area have lower connectivity and higher causality, also possessing their independence. They may influence a few other factors and are considered the second priority for the utilization of management resources. According to the analysis results of this study, the following factors are listed as second priority:

- Stability and accuracy support of hospital information systems

- Personal data security management

- Ease of operation of medical equipment interfaces

- Support and professional competence of medical personnel

- Full support of hospital management

- Clear policies and regulations

While analyzing the critical success factors for telemedicine outpatient services, "core factors" and "driving factors" are two important concepts with distinct differences. Core factors refer to the essential conditions and key elements necessary for the successful operation of telemedicine. Liu Jian-Tsai and Chen Jui-Sung (1997) showed that primary healthcare institutions can establish a support network with medical centers through telemedicine, improving their own medical service quality to meet patient needs. Medical centers or regional hospitals providing teleconsultation services not only assist in medical care for remote areas but also reduce the time specialized doctors spend visiting primary healthcare institutions. This helps improve the quality of medical services in remote areas, achieving the goal of health equity, enabling residents in rural areas to receive high-quality medical services. In practice, core factors and driving factors often need to coordinate with each other. For example, core factors provide a stable foundation for implementing telemedicine, such as supplier technical stability and proper education and training, while driving factors determine whether the service can rapidly expand the market and realize its value. Once core factors are established, enterprises or related organizations can focus on promoting the growth of driving factors, thereby increasing the value of telemedicine outpatient services. By simultaneously focusing on core factors and driving factors, telemedicine outpatient services can achieve short-term success and realize long-term sustainable development.

Quadrant III: Effect factors of perceived risks:

According to the analysis of the questionnaire results collected in this study, no independent factors were identified, and there were no mutual influence factors among the dimensions of this study.

Quadrant IV: Effect factors of perceived:

According to the characteristics of the influenced factors area, the factors located here have higher connectivity and lower causality. These factors are urgent but cannot be directly improved; usually, managing Quadrants I and II well can indirectly improve the factors in this area. They are the lowest priority for the utilization of management resources. Based on the results of this study, the key influenced factors in this area are: b. Information literacy of hospital medical personnel, h. Cooperation of administrative staff, and k. Referral and follow-up medical support mechanisms.

- Information literacy of hospital (medical) personnel:

In the process of promoting telemedicine outpatient services in rural areas, if the information literacy of hospital medical personnel is regarded as an "influenced factor," it implies that information literacy is not a fixed state but a dynamically growing element. Positioning the information literacy of medical personnel as an "influenced factor" suggests that the digital capabilities and application skills of medical personnel in telemedicine can be altered or enhanced through external training, software and hardware resource support, work design, and incentive measures.

- Cooperation of administrative staff:

In the process of promoting telemedicine outpatient services in rural areas, categorizing "cooperation of administrative staff" as an influenced factor indicates that the degree of cooperation from administrative staff is one of the critical elements for the effectiveness of telemedicine outpatient services. From this perspective, the significance of "cooperation of administrative staff" as an influenced factor lies in its reflection of the system's operational integration, the adequacy of environmental support, and the effectiveness of team collaboration. To increase the success rate of telemedicine outpatient services in rural areas, creating a favorable environment and management mechanism that promotes active participation and efficient cooperation among administrative staff is essential.

- Referral and follow-up medical support mechanisms:

In the context of promoting telemedicine in rural areas, viewing "referral and follow-up medical support mechanisms" as an influenced factor implies that the effectiveness or operation of this factor is subject to other preconditions or factors. This perspective helps clarify the key challenges and success elements of telemedicine. The capability or efficiency of "referral and follow-up medical support mechanisms" depends on the telemedicine system itself and its related infrastructure, such as medical resource allocation, data sharing, and basic infrastructure. If the telemedicine system lacks in aspects such as technology, management, or human resources, it may lead to poor integration of the referral and follow-up medical chain. The challenges of cross-institutional collaboration also affect referral and follow-up medical support mechanisms, requiring cooperation and resource integration among multiple medical institutions. Thus, this analysis perspective allows us to see deeper issues and focus efforts on improving the crucial elements that determine the success of telemedicine, rather than merely addressing superficial phenomena.

Limitations and Further Research

Limitations:

(a) Data Collection Limitations: Data may originate from specific regions or medical institutions, and the sample may lack broad representativeness. Selection bias among participants may affect the results.

(b) Subjective Bias: The DEMATEL research method primarily relies on expert opinions, which inevitably introduce personal biases, directly affecting the objectivity of the assessment.

(c) Simplification of Complex Relationships: Since DEMATEL uses a matrix form to represent the relationships between factors, some complex interactions may be simplified or overlooked.

(d) Time and Resource Constraints: Conducting a comprehensive and vivid DEMATEL analysis requires substantial time and resources, potentially limiting the depth of data collection and analysis.

(e) Consideration of Factor Dimensions: There may be unrecognized or unaccounted-for factors of failure or success that were not included in the analysis.

Future Research:

(a) Multi-region and Multi-institution Studies: Conduct data collection across different regions and various types of medical institutions to enhance the generalizability of the research findings.

(b) Incorporation of Quantitative Data: Combining quantitative and qualitative data can provide a more objective and comprehensive analysis.

(c) Integration of Other Research Methods: Utilize other multi-criteria decision analysis methods, such as ANP and AHP, to gain a more comprehensive understanding of the complex relationships between factors.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

This study has been approved by the authorized institution's Institutional Review Board (IRB) (No. TYGH113051, IRB approval Date: 2024/12/2).

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

We sincerely appreciate the valuable contributions provided by the professionals from the case hospital for this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- bdurakhmanovich KO & Farrukhkhonovna DM. The role of the regional telemedicine center in the provision of medical care. Cyberlininka.ru 3 (2023): 160-165.

- Bai, Li. "Recommendations for the Prospective Development of Smart Technology in Elderly Living and Care Applications," Journal of Welfare Technology and Service Management 6 (2018): 21-37.

- Bashshur RL, Shannon GW & Krupinski EA. The empirical evidence for the telemedicine intervention in the management of chronic diseases. Telemedicine and e-Health 17 (2011): 103-108.

- Boynton AC & RW Zmud. An assessment of critical success factors. Sloan management review 25 (1984): 17-27.

- Broens TH, et al. Determinants of successful telemedicine implementations: a literature study, Journal of telemedicine and telecare 13 (2007): 303-309.

- Buck S. Nine human factors contributing to the user acceptance of telemedicine applications: a cognitive- emotional approach. Journal of telemedicine and telecare 15 (2009): 55-58.

- Chen, Peng-Ting, Hsieh, Yu-Kuang. "Exploring the Development of Telecare Services by Integrating ICT in Medical Institutions," Journal of Technology Management 16 (2011): 1-40.

- Cheng, Yong-Ming, Shih, Bo-Zhou. "Key Success Factors for Implementing PACS in Medical Centers," Performance and Strategy Research 3 (2006): 79-99.

- Chute AG, Thompson MM & Hancock BW. The McGraw-Hill handbook of distance learning. New York: McGraw (1999).

- Cilliers L. Critical success factors for telemedicine centres in African countries, University of Fort Hare 5 (2010): 150.

- Clark M, et al. Sustaining innovation in telehealth and telecare, WSD Action Network, King's Fund (2010).

- Cook et al. Administrator and provider perceptions of the factors relating to programme effectiveness in implementing telemedicine to provide end-of-life care, Journal of telemedicine and telecare 7 (2001): 17-19.

- Daniel DR. Management information crisis, Harvard Business Review 39 (1961): 111-121.

- Deldar, et al. Teleconsultation and Clinical Decision Making: a Systematic Review. Acta Informatica Medica 24 (2016): 286-292.

- Dorsey ER, Topol EJ & State of Telehealth. State of telehealth. New England Journal of Medicine 375 (2016): 154-161.

- Fontela E, & Gabus A. The DEMATEL Observer, DEMATEL 1976 Report. Switzerland, Geneva: Battelle Geneva Research Center (1976).

- He, Bing-Hua, Huang, Zhu-Cen, Liu, Yu-Sheng. "Exploring Key Success Factors for Telemedicine Implementation," Cheng-Ching Journal of Health and Hospital Management 17 (2021): 27-36.

- Hossein Ahmadi, et al. Evaluation the factors affecting the implementation of hospital information system (HIS) using AHP, Life Science Journal 11 (2014): 202-207.

- Huang Hui-Wen, Report on the Current Situation of Medical Care in Rural and Offshore Areas in Taiwan By Ministry of Health and Welfare, Taiwan (2020).

- Hou, Yi-Li, Wu, Chia-Ying, et al. "Application of Real-time Teleconsultation in Rural Areas: Sharing the Experience of the Department of Dermatology at Kaohsiung Chang Gung Memorial Hospital," Taiwan Medical Journal 66 (2023): 47-49.

- Hsu KF, Huang PL, Lee TS, & et al. Analysis of Taiwan Emergency Physicians’ Core Competencies Based on ACGME Criteria. Sage Journals 13 (2023):

- Hsu, Yu-Ping. "What is Telemedicine? Comprehensive Overview of the Current Status, Regulations, and Policies of Telemedicine in Taiwan," Future City (2022).

- Jian, Yu-Ning, Chen, Ting-An, et al. Exploring How to Improve the Effectiveness of Medical Services and Care in Areas with Insufficient Healthcare Resources under National Health Insurance – A Case Study of Western Medical Services (Project Number: M08P1109), Ministry of Health and Welfare unpublished (2019).

- Joseph V, et al. Ke challenges in the development and implementation of telehealth projects, Journal of Telemedicine and Tlecare 17 (2011): 71-77.

- Judi H. et al. Feasibility and critical success factors in implementing telemedicine, Information Technology Journal 8 (2009): 326-332.

- Kodukula S & M Nazvia. Evaluation of critical success factors for telemedicine implementation, Evaluation 12 (2011): 8-15.

- Lee PC & Hou L. Where is the Future of Taiwan National Health Insurance's Tiered Medical Care System Heading? Angle Health Law Review 87 (2024).

- Leidecker JK & AV Bruno. Identifying and using critical success factors, Long Range Planning 17 (1984): 23-32.

- Li, Bo-Zhang, Hsu, Ming-Hui, et al. Challenges and Strategies for Developing Telehealth Care, Taipei: Chung-Hwa Institution for Economic Research (2023).

- Li, Zhuo-Lun, Chen, Wen-Yi, et al. "Current Status and Challenges of Developing Telehealth in Taiwan," Journal of Medicine and Health 2 (2013): 1-10.

- Liu C-F. Key factors influencing the intention of telecare adoption: An institutional perspective, Telemedicine and e-Health 17 (2011): 288-293.

- Liu, Jian-Tsai, Chen, Rui-Song. "Application of Teleconsultation Systems in Primary Healthcare," Taiwan Medical Journal 1 (1997): 612-616.

- Liu, Meng-Fen. Exploring the Benefits of Telecare in Rural Health Promotion: A Case Study of the WeCare Telehealth Platform, Executive Master's Thesis, National Chengchi University Executive MBA Program, Taipei (2022).

- Miller et al. Telehealth: A clinical application model for rural consultation. Journal of Practice and Reasch 55 (2003): 119-127.

- Mousavi Baigi et al. Challenges and opportunities of using telemedicine during COVID-19 epidemic: A systematic review, Frontiers in Health Informatics 11 (2022): 1-9.

- Obstfelder A, et al. Characteristics of successfully implemented telemedical applications, Implement Science 2 (2007): 1-11.

- Organization WH & WH Organization. A Health Telematics Policy in Support of WHO's Health-For-All Strategy for Global Development. Report of the WHO Group Consultation on Health Telematics, Geneva, World Health Organization (1998).

- Qiu, Shu-Ti, McMahon. Health Inequality Report in Taiwan, Taipei: Health Promotion Administration, Ministry of Health and Welfare (2017).

- Pollalis YA, & Frieze IH. A new look at CSF In IT, information strategy. Exec J 18 (1993): 25-32.

- Rockart JF. Chief executives define their own data needs, Harvard business review 57 (1978): 81-93.

- Steventon A, et al. Effect of telehealth on use of secondary care and mortality: findings from the Whole System Demonstrator cluster randomised trial, British Medical Journal 344 (2012).

- Taneja U. Critical Success Factors for eHealthcare. eTELEMED 2013, The Fifth International Conference on eHealth, Telemedicine, and Social Medicine (2013).

- Tamura H & Akazawa K. Stochastic DEMATEL for structural modeling of a complex problematique for realizing safe, secure and reliable society. Journal of telecommunications and information technology (2005): 139-146.

- Tzeng GH, Chiang CH & Li CW. Evaluating intertwined effects in e-learning programs: A novel hybrid MCDM model based on factor analysis and DEMATEL. Expert Systems with Applications 32 (2007): 1028-1044.

- Tjosvold D. Conflict within interdependence: Its value for productivity and individuality, in De Dreu, C. K. W., & Van de Vliert E. (Eds), Using Conflict in Organization (1997): 23-37.

© 2016-2025, Copyrights Fortune Journals. All Rights Reserved