Malaria Prevalence and Diagnostic Accuracy of Rapid Diagnostic Tests Versus Microscopy in Children (1–15 Years) in Cite Verte Health District, Cameroon

Takamo Peter*, 1, 2, Baiye Williams Abange2, Fankoua Tchaptchet Luc Baudoin1, Elvis Asangbeng Tanue1, Ntumwil Thomas Toah1, Ghislain Dema1, 2, Aboudou Mbom Marie-Ange1, Enoh Junior Enoh1, 3, Babilla Isabelle Becky Nagwah1, 3, Arole Darwin Touko1, Tanyi pride Bobga1, 2, Abdel Jelil Njouendou3

1Department of Public Health and Hygiene, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon.

2Department of Medical Laboratory science, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon.

3Department of Biomedical Science, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon.

*Corresponding Author: Takamo Peter, Department of Public Health and Hygiene, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Buea, P.O. Box 63, Buea, Cameroon.

Received: 11 October 2025; Accepted: 21 October 2025; Published: 05 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Takamo Peter, Baiye Williams Abange, Fankoua Tchaptchet Luc Baudoin, Elvis Asangbeng Tanue, Ntumwil Thomas Toah, Ghislain Dema, Aboudou Mbom Marie-Ange, Enoh Junior Enoh, Babilla Isabelle Becky Nagwah, Arole Darwin Touko, Tanyi pride Bobga, Abdel Jelil Njouendou. Malaria Prevalence and Diagnostic Accuracy of Rapid Diagnostic Tests Versus Microscopy in Children (1–15 Years) in Cite Verte Health District, Cameroon, Fortune Journal of Health Sciences. 8 (2025): 1136-1142.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Malaria is a life threatening disease caused by Plasmodium parasites which are transmitted through the bite of and infected female Anopheles mosquitoes. Malaria is one of the serious public health issues and causes of morbidity and mortality including suffering in tropical and sub-tropical regions. This study aims to determine Malaria Prevalence and Diagnostic Accuracy of Rapid Diagnostic Tests Versus Microscopy in Children (1–15 Years) in Cite Verte Health District.

Method: A cross-sectional study was conducted among 150 children aged 1-15 years who were chosen using convenient sampling technique. Descriptive statistics was used to present the frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. The chi-square test of independence was also used to show statistical significance. The Sensitivity, specificity, positive, negative predictive value was used to compare microscopy and RDT.

Results: Participants mean age was 5.5 years (SD = 4.4). Malaria prevalence in children was 24% using the gold standard technique (Microscopy) and 16.7% using RDT. The Microscopy test results had a significant agreement with RDTs (kappa = 0.776, p=0.001) indicating RDTs could serve as a reliable alternative to microscopy when diagnosing malaria. The RDT had very high specificity (100%) and an ideal positive predictive value (PPV=100%), as indicated by the fact that all the positive tests had no errors in determining malaria. It however, did not detect 30.6% of the actual malaria cases (sensitivity = 69.4%). In general, it identified 92.7% of the cases correctly.

Conclusion: The malaria prevalence rate in this study reflects the heavy burden of malaria in the urban area. These results also highlight the strength of RDTs as a fast diagnostic test in limited resources settings especially in positive cases confirmation, and the importance of microscopy in identifying false-negative cases in symptomatic children.

Keywords

Prevalence, Malaria, Microscopy, RDT, Cameroon

Article Details

Introduction

Malaria is a life-threatening disease caused by Plasmodium parasites which are transmitted through the bite of and infected female Anopheles mosquitoes to the human body. It is widespread in the sub-Saharan part of the world and other tropical areas across the globe [1]. Malaria is a severe health concern and is one of the leading causes of morbidity and mortality among the pediatric population of sub-Saharan Africa, with a disproportionate burden among thechildren below the age of 15. More than 2 million cases are reported every year in Cameroon, and children are of the most severe outcomes and mortality [2,3]. Plasmodium includes 123 known species. But five of them are known to develop infections in human beings. Plasmodium falciparum is the most prevalent and harmful malaria species. It causes a huge amount of malaria related deaths [4,5]. Mosquitoes are mainly found within the subtropical and tropical regions of the globe [6]. When a person has malaria, he or she can experience fever, muscle pains and chills in case of non-severe malaria [1]. Nevertheless, in children below five years, there is a presentation of severe malaria, which could include reduced level of consciousness, fever, respiratory distress, severe anemia, convulsions, hypoglycemia among many others [5]. The symptoms often occur after the first mosquito bite, usually between 10-15 days. Some cases of infections with certain strains of plasmodium vivax, may have delayed symptoms by 8-10 months or more [7]. Half of the world population mostly in the African continent is vulnerable to malaria and suffering economically due to the disease. WHO in 2021, reported 247 million malaria cases and 619, 000 deaths of which 234 million cases and 593, 000 deaths were recorded in Africa. Moreover, about 79 % of the deaths occurred among children below five years [8]. Nevertheless, even despite the current achievements in the malaria combat, this issue remains prevalent [9]. It has been cited among the top three causes of deaths in the healthcare facilities in Cameroon with a 30 % ratio of the death [10]. Global malaria burden varies geographically due to the intensity of the malaria transmission of the area [11]. Malaria control cannot be effective without accurate diagnosis. Although microscopy is the gold standard, it needs trained staff and infrastructure which might be unavailable in low resources areas. Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) provide an easier alternative but their sensitivity depends on the setting, population and density of the parasites [12]. Though the World Health Organization recommends the use of parasitological confirmation prior to treatment, in most settings in Cameroon, the use of clinical diagnosis or untested RDTs is being used. There have been mixed sensitivity of RDTs with reported cases of RDTs being inconsistent especially in case of asymptomatic carriers or low-parasitemia. There are limited data of urban data on diagnostic performance among children [13,14]. This study is aimed at determining Malaria Prevalence and Diagnostic Accuracy of Rapid Diagnostic Tests Versus Microscopy in Children (1–15 Years) in Cite Verte Health District.

Materials and Methods

Study design and settings

This hospital-based cross-sectional study was carried out in Cite-Verte health district Hospital located at the center region of Cameroon, from February to April, 2022. Yaoundé is the capital city of Cameroon with a population estimate of 2.5 million people. It has an elevation of about 750 meters (2,500 ft) above sea level. This area has an average 23.7oC temperature and an average annual rain of 1643 mm. In Yaounde, the transmission of malaria is holoendemic and seasonal and Anopheles gambiae is the most predominant vector [15].

Study population and sampling

This study used a convenient sampling approach to recruit a total of 150 children aged 1-15 years visiting Cite-Verte health district Hospital located at the center region of Cameroon. The sample size was calculated using the Cochran’s formula.

abcFor a z-value of 1.96 as the standard normal variate at 95% confidence level, error margin of 5% (e), and a prevalence of 9.1% [16]. A minimum sample size of 150 participants were recruited

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Inclusion criteria

Children aged 1-15 years visiting the Cite-Verte health district Hospital

Exclusion criteria

Children aged 1-15 years visiting the Cite-Verte health district Hospital who were on anti - malaria medications

Laboratory methods

In order to identify malaria parasite by microscopy, venous blood was collected using EDTA tubes. Thick and thin (for species identification) blood films were prepared and allowed to air dry. the thin film was fixed with methanol for 3 to 10 seconds to maintain the morpholology of the red cells. The slide were then stained for 10 to 15 minutes with Giemsa diluted 1:10 and washed under tap water and dried. The slides were covered with immersion oil covering areas of about 10mm in diameter of the films. Both thick and thin films were observed under oil immersion (x100) of the microscope. The prepared slide were then observed under the microscope by experienced medical laboratory scientist. The Malaria parasite count was done as such: Number of parasites x 8000/Number of leucocytes counted. The slide were also randomly cross checked by three laboratory scientists. A malaria rapid diagnostic test was also performed using the CareStartTM RDT, which were kept in conditions as required by the manufacturer, in a cool, dry condition with a constant temperature (2°C - 30°C). All RDTs were within their approved expiry date. Strict quality control was maintained by use of visual inspection before use.

Data management and analysis

The data collected from participants were anonymized to maintain confidentiality. The data was cleaned with Microsoft excels 2016 and imported to the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS version 26) and analyzed. Descriptive statistics was used to present the frequencies and percentages for categorical variables. Statistical significance was set at p < 0.05. Diagnostic performance was examined through Sensitivity, specificity, positive and negative predictive values.

Declarations

Ethical consideration

The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the Faculty of Health Sciences of the University of Buea (IRB FHS-UB), followed by an administrative authorization from the cite verte district hospital. The research was in line with the ethical requirements of studies on humans, following the Helsinki Declaration.

Consent to participate

Potential participants were told the aims and benefits of contributing to the study. Both the consent of the guardian and participant assent forms were signed before enrollment of the participants. Study Participants were free to drop out at any point.

Consent to publish

All authors declare that the study participants gave consent to publication of the data collected in this study.

Results

Distribution of malaria in relation to age and sex

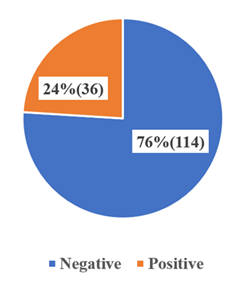

The distribution of malaria infection by age groups and genders, showed a differences in the prevalence. Among the 1–5 year age group (children), a higher rate of infection (6.7%) was observed in females versus males (4%). Similarly, for children in the 6–10 year age group, female prevalence (5.3%) was higher than that in males (3.3%). However, for the 11–15 years adolescent age group, malaria infection was marginally higher in males (2.7%) than females (2%) (Table 1). Generally, overall prevalence was higher in females (14%) than in males (10%). Out of the 150 individuals 36(24%) tested positive for malaria by microscopy (figure 1).

Prevalence of malaria according to the age and sex by RDT and Microscopy

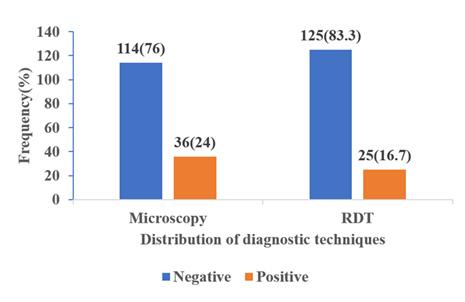

Malaria prevalence in respect to age and sex was determined in both Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDT) and microscopy. Regarding RDT, the highest rates of males were recorded in children aged between 6 to 10 years (34.2%), 11 to 15 years (28%) and 1 to 5 (18.4), but the differences were not statistically significant. The prevalence differed slightly between the sexes with those of the females (26.6%) being higher than those of the males (21.1%) yet the difference was not significant (Table 2). Results of microscopy demonstrated a similar trend with the highest prevalence in the 6-10 years group (23.7%), followed by the 11-15 years (16%) and the 1-5 years (13.8%), although, all these results were not statistically significant. Female subjects were again at a slightly higher rate of infection (17.7%) compared with males (15.5%) but this was not significant (Table 3). The Microscopic technique identified 36(24%) out of the 150 participants to be positive for malaria, while RDT showed 25(16.7%) (figure 2).

Distribution of Plasmodium Species Among Infected Children (1-15 Years)

The most common malaria parasite observed among each of the age groups was the Plasmodium falciparum with the highest prevalence (31.6%) in children less than 10 years of age (6-10 years), 11-15 years (24%) and 1-5 years (18.4%). Only 2.6% of the cases in age group 6-10 years and 4% of the cases in the age group between 11 and 15 years had P. malariae and none had P. ovale or P. vivax parasite (Table 4).

Diagnostic accuracy of Rapid Diagnostic Tests Compared to Microscopy

Microscopy and RDTs had significant agreement (k = 0.776, p=0.001) indicating RDTs could serve as a reliable alternative to microscopy when diagnosing malaria (Table 5a). The RDT had very high specificity (100%) and an ideal positive predictive value (PPV=100%), as indicated by the fact that all the positive tests had no errors in determining malaria. It however, did not detect 30.6% of the actual malaria cases (sensitivity = 69.4%), hence the falsely negative results needed additional microscopy on patients with symptoms of malaria. In general, it identified 92.7% of the cases correctly (Table 5b).

Table 1: Distribution of malaria in relation to age and sex

|

Age(years) |

Number examined |

Number infected |

Prevalence(%) |

|||

|

Females |

Males |

Females |

Males |

Females |

Males |

|

|

1-5. |

47 |

40 |

10 |

6 |

6.7 |

4 |

|

11-15. |

14 |

11 |

3 |

4 |

2 |

2.7 |

|

6-10. |

18 |

20 |

8 |

5 |

5.3 |

3.3 |

|

Total |

79 |

71 |

21 |

15 |

14 |

10 |

Table 2: Prevalence of malaria according to the age and sex by RDT

|

Parameter |

Number examined |

Prevalence |

p.value |

|

Age(years) |

|||

|

1-5. |

71 |

16(18.4) |

|

|

11-15. |

18 |

7(28) |

0.143 |

|

6-10. |

25 |

13(34.2) |

|

|

Sex |

|||

|

Female |

58 |

21(26.6) |

0.434 |

|

Male |

56 |

15(21.1) |

Table 3: Prevalence of malaria according to the age and sex by Microscopy

|

Parameter |

Number examined |

Prevalence |

p.value |

|

Age(years) |

|||

|

1-5. |

75 |

12(13.8) |

|

|

11-15. |

21 |

4(16) |

0.392 |

|

6-10. |

29 |

9(23.7) |

|

|

Sex |

|||

|

Female |

65 |

14(17.7) |

0.827 |

|

Male |

60 |

11(15.5) |

Table 4: Distribution of Plasmodium Species Among Infected Children (1-15 Years)

|

Variation in years |

1-5. |

6-10. |

11-15. |

|||

|

Species of plasmodium |

NO. Positive |

% |

NO. Positive |

% |

NO. Positive |

% |

|

P. Falsciparum |

16 |

18.4 |

12 |

31.6 |

6 |

24 |

|

P. Malariae |

0 |

0 |

1 |

2.6 |

1 |

4 |

|

P. Ovale |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

P. Vivax |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

|

Examined number |

16 |

18.4 |

13 |

34.2 |

7 |

28 |

Table 5a: Diagnostic accuracy of Rapid Diagnostic Tests Compared to Microscopy

|

Microscopy |

||||||

|

Negative |

Positive |

Total |

Kappa |

P.value |

||

|

RDT |

Negative |

114 |

11 |

125 |

||

|

Positive |

0 |

25 |

25 |

0.776 |

0.001 |

|

|

Total |

114 |

36 |

150 |

|||

Table 5b: Diagnostic accuracy of Rapid Diagnostic Tests Compared to Microscopy

|

Method |

Specificity (%) |

Sensitivity (%) |

PPV (%) |

NPV (%) |

Accuracy (%) |

|

RDT |

100 |

69.4 |

100 |

91.2 |

92.7 |

|

Microscopy (reference) |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

100 |

Discussion

The prevalence of malaria among the urban Cameroonian children in the Cite Verte Health District was high, 24%. When compared with Microscopy, Rapid Diagnostic Tests (RDTs) had high specificity (100%) and moderate sensitivity (69.4%), which indicates that it may be useful to confirm malaria however would not be able to rule out the infection in all cases.

Prevalence of Malaria In Children Aged 1-15 Years

This present study determined the prevalence of malaria in children to be 24% in the Cite Verte Health District center region of Cameroon, using microscopy as the gold standard. This prevalence is aligned with the regional statistics in Cameroon whereby malaria is one of the key social health issues especially in children. According to a systematic review, 24% prevalence in 2017 was the national malaria prevalence, which was below the 41% prevalence in 2000, as a result of the increased vector control intervention that included long-lasting insecticidal nets (LLINs) [17]. Nevertheless, the burden of prevalence among children greatly differs between the epidemiological strata of the Cameroon population since they vary with the intensity of the transmission, ecological conditions, and even coverage of interventions [18]. A 46.9% prevalence of asymptomatic malaria was identified in children aged between 3 and 15 years in Cameroon in the North Region during the rainy season [17]. In the same manner, a prevalence of 31.5% among children younger than 15 years (5-15) was observed in the region of Mount Cameroon [19]. The high prevalence maybe due to geographic location or high transmission intensity. A study undertaken in Nigeria showed a prevalence of 34.7% in children under the age of 15 years in a high-transmission rural area [20]. In a study in Papua New Guinea an area of high transmission outside Africa, among children aged 5 to 15 years, the prevalence rate was 33.7% [21]. These lower prevalence compared to these same rural and high-transmission settings might be an indication of urban benefits, where the LLIN access (86.36% ownership in Cameroon) and the healthcare services availability may be associated with better chances of seeking treatment [22]. However, the prevalence rate of 24% shows that malaria is a severe burden in Cameroon cities, and there is a need to keep the control constant.

Diagnostic Accuracy of Rapid Diagnostic Tests Compared to Microscopy

Microscopy and RDTs had significant agreement (k = 0.776, p=0.001) indicating RDTs could serve as a reliable alternative to microscopy when diagnosing malaria. The RDT had very high specificity (100%) and an ideal positive predictive value (PPV=100%), as indicated by the fact that all the positive tests had no errors in determining malaria. It however, did not detect 30.6% of the actual malaria cases (sensitivity = 69.4%). In general, it identified 92.7% of the cases correctly, which reinforces the value of the RDT in resource-constrained countries, but its use should be accompanied by microscopy to validate negative RDT decisions in symptomatic patients. The moderate sensitivity could indicate low-density parasitemia in partially immune children or the deletion of HRP2 gene, which decreases the antigen sensitivity. There are also operator technique and the environmental storage conditions that can affect test performance. These results are similar with other literature in Cameroon and Africa. A study in the Mount Cameroon area undertaking the assessment of Partec CyScope fluorescence-based RDT demonstrated a sensitivity of 87.6% and a specificity of 94.9%, a PPV of 97.1%, and a negative predictive value (NPV) of 79.6% against microscopy [23]. The increased sensitivity in the said study is possibly due to the fact that the fluorescence based RDT detected low-density parasitemia. Conversely, RDT sensitivity of 90.6% and specificity of 57.1%, compared to PCR as the reference test, suggests the limitations of RDTs in identifying sub-microscopic infection [18]. A meta-analysis of RDT performance on children younger than 5 discovered a pooled sensitivity of 92% and specificity of 96.6% to diagnose Plasmodium falciparum in all low-income countries, demonstrating that RDTs are likely to be reliable, but with a reduced sensitivity when it comes to the low-density infection [24]. This reduced sensitivity (69.4%) in the present study relative to these reports, may be a consequence of difficulty in the detection in low density or asymptomatic infections that are dominant in Cameroon with high asymptomatic carriage [17]. RDTs are still important in the context of triaging of febrile children in resource-limited settings. Nevertheless, they should be accompanied by microscopy whenever possible, especially in positive cases that are symptomatic because they will prevent missed diagnosis and ongoing transmission. These results highlight the importance of integrated approaches to diagnostics, which integrates the convenience of RDTs and confirmatory microscopy. Future studies are required to examine how parasite load and gene deletion can influence test performance across varying transmission areas.

Limitations

The convenience sampling technique we have used restricts the applicability of our study on the larger population of children in Cite Verte Health District because the sample is likely to be biased by the method of selection.

Conclusion

These findings highlight the strength of RDTs as a fast diagnostic test in limited resource settings especially in positive cases confirmation, and the importance of microscopy in identifying false-negative cases in symptomatic children. The findings support the use of comprehensive diagnostics that can go hand in hand with RDTs and microscopy to contribute towards better case management and minimizing untreated infections. In order to decrease the occurrence of malaria further, the initiation of sustained impacts on vector management, community training, and research into variables influencing the sensitivity of the RDT are advised. The findings are relevant in building the evidence towards the use of the malaria diagnosis and control strategies in optimizing urban Cameroon and other endemic similar regions.

Funding Declaration: There was no funding

Data availability: Data will be made available by authors on reasonable request.

Abbreviations

LLINs Long Lasting Insecticidal Nets

RDT Rapid Diagnostic Test

PPV Positive Predictive Value

NPV Negative Predictive Value

References

- Iyaniwura SA, Han Q, Yong NB, et al. Regional variation and epidemiological insights in malaria underestimation in Cameroon. Infectious Disease Modelling (2025).

- Cheesbrough M. District laboratory practice in tropical countries, part 2. Cambridge university press (2005).

- Egbom S, Nduka FO, Nzeako SO, et al. SPATIAL DISTRIBUTION OF MALARIA AND LAND COVER PATTERNS IN OGONI LAND, RIVERS STATE, NIGERIA. Malaysian Journal of Science 30 (2023): 92-100.

- Bakary T, Boureima S, Sado T. A mathematical model of malaria transmission in a periodic environment. Journal of biological dynamics 12 (2018): 400-32.

- Beretta E, Capasso V, Garao DG. A mathematical model for malaria transmission with asymptomatic carriers and two age groups in the human population. Mathematical biosciences 300 (2018): 87-101.

- Dalrymple U, Mappin B, Gething PW. Malaria mapping: understanding the global endemicity of falciparum and vivax malaria. BMC medicine 13 (2015): 140.

- Kotepui M, Kotepui KU, Milanez GD, Masangkay FR. Prevalence and risk factors related to poor outcome of patients with severe Plasmodium vivax infection: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and analysis of case reports. BMC Infectious Diseases 20 (2020): 363.

- World Health Organization. Global technical strategy for malaria 2016-2030. World Health Organization (2015).

- Massoda Tonye SG, Kouambeng C, Wounang R, et al. Challenges of DHS and MIS to capture the entire pattern of malaria parasite risk and intervention effects in countries with different ecological zones: the case of Cameroon. Malaria journal 17 (2018): 156.

- Plan stratégique National de lutte contre le paludisme au Cameroun 2014–2018.

- Kogan F. Malaria burden. InRemote sensing for malaria: Monitoring and predicting malaria from operational satellites 21 (2020): 15-41.

- Opoku Afriyie S, Addison TK, Gebre Y, et al. Accuracy of diagnosis among clinical malaria patients: comparing microscopy, RDT and a highly sensitive quantitative PCR looking at the implications for submicroscopic infections. Malaria Journal 22 (2023): 76.

- Mfuh KO, Achonduh-Atijegbe OA, Bekindaka ON, et al. A comparison of thick-film microscopy, rapid diagnostic test, and polymerase chain reaction for accurate diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum malaria. Malaria journal 18 (2019): 73.

- Kennedy TW, Otokunefor K. Diagnostic efficiency of rapid diagnosis test kits in malaria diagnosis—the nigerian story. Gazette Of Medicine 5 (2017): 1-5.

- Njunda AL, Njumkeng C, Nsagha SD, et al. The prevalence of malaria in people living with HIV in Yaounde, Cameroon. BMC public health 16 (2016): 964.

- Akindeh NM, Ngum LN, Niba PT, et al. Assessing asymptomatic malaria carriage of Plasmodium falciparum and non-falciparum species in children resident in Nkolbisson, Yaoundé, Cameroon. Children 8 (2021): 960.

- Antonio-Nkondjio C, Ndo C, Njiokou F, et al. Review of malaria situation in Cameroon: technical viewpoint on challenges and prospects for disease elimination. Parasites & vectors 12 (2019): 501.

- Kwenti TE, Kwenti TDB, Njunda LA, et al. Identification of the Plasmodium species in clinical samples from children residing in five epidemiological strata of malaria in Cameroon. Tropical medicine and health45 (2017): 1-8.

- Teh RN, Sumbele IU, Meduke DN, et al. Malaria parasitaemia, anaemia and malnutrition in children less than 15 years residing in different altitudes along the slope of Mount Cameroon: prevalence, intensity and risk factors. Malaria journal 17 (2018): 336.

- Ojurongbe O, Adegbosin OO, Taiwo SS, et al. Assessment of clinical diagnosis, microscopy, rapid diagnostic tests, and polymerase chain reaction in the diagnosis of Plasmodium falciparum in Nigeria. Malaria research and treatment (2013): 308069.

- Mueller I, Galinski MR, Tsuboi T, et al. Natural acquisition of immunity to Plasmodium vivax: epidemiological observations and potential targets. Advances in parasitology 81 (2013): 77-131.

- Mbishi JV, Chombo S, Luoga P, et al. Malaria in under-five children: prevalence and multi-factor analysis of high-risk African countries. BMC Public Health 24 (2024): 1687.

- Ndamukong-Nyanga JL, Kimbi HK, Sumbele IU, et al. Comparison of the Partec CyScope® rapid diagnostic test with light microscopy for malaria diagnosis in rural Tole, Southwest Cameroon.

- World Health Organization. Fact sheet about malaria. WHO (2024).