Pointless Yoyo-Perfusion Mode in CPR: Potential Proposals

Sayed NOUR

Biosurgical Research Laboratory, Alain Carpentier Foundation, Pompidou Hospital, Paris-Cité University, Paris, France

*Corresponding Autho: Sayed NOUR, Biosurgical Research Laboratory, Alain Carpentier Foundation, Pompidou Hospital, Paris-Cité University, Paris, France

Received: 23 November 2025; Accepted: 26 November 2025; Published: 05 December 2025

Article Information

Citation: Sayed NOUR. Pointless Yoyo-Perfusion Mode in CPR: Potential Proposals. Fortune Journal of Health Sciences. 8 (2025): 1143-1152.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Background: Cardiac arrest (CA) is a hemostatic state only reversible via dynamic intracardiac action potentials following hemorheological–biochemical reactions of adequate blood volumes (BVs). Undeniable electrophysiological processes begun since intrauterine life compromised by cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR). Apart from mechanical circulatory support (MCS), CPR induces an ineffective back-and-forth perfusion mode that worsens the stalled cellular metabolism. This is probably due to the arrested cardiopulmonary pumps—the main generators of endothelial shear stress (ESS) that control microcirculation, thereby, cellular metabolism.

Objectives: The goal is to highlight and address shortcomings of CPR, including its incompatibilities with human cardiotorsal anatomy and thoracic biomechanics.

Method: Prompt ESS restorations: mechanically with a noninvasive MCS inducing pulsatile circulatory flow restoration (CFR) regardless of return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC). And manually, with a novel chest compression technique allowing refill-recoil–rebound (3R/CPR) the heart and ribcage in a near-circumferential manner through the left 5th intercostal space. The technique can provide adequate BV inducing intracardiac water hammer-like mechanism and atrial wall stress promoting less traumatic ROSC.

Results: Obtained data shown significant improvement of tissue perfusion with CFR device in CA animal models and the potential advantages of 3R/CPR following its inevitable applications in two drownings after unsuccessful CPR. Additionally, an invasive pulsatile MCS data shown significant advantages of ESS-mediated endothelial function restoration over steady-flow perfusion in beatless-heart model.

Conclusions: Prompt ESS restoration can preserve cellular metabolism during CA. In-depth analysis of the proposal could evolve the strict doctrine of CPR, thus opening new horizons to improve the dismal outcomes of victims.

Keywords

Cardiac arrest (CA), Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR), Circulatory flow resuscitation (CFR), Endothelial dysfunction, Endothelial shear stress (ESS), Mechanical circulatory support (MCS), Microcirculation

Cardiac arrest (CA) articles, Cardiopulmonary resuscitation (CPR) articles, Circulatory flow resuscitation (CFR) articles, Endothelial dysfunction articles, Endothelial shear stress (ESS) articles, Mechanical circulatory support (MCS) articles, Microcirculation articles.

Article Details

Introduction

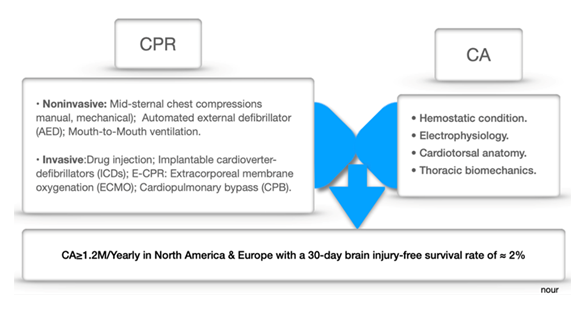

Cardiac arrest (CA) still claims a staggering number of lives annually, having caused widespread disabilities over the six decades since CPR was first employed [1,2]. Current CPR modalities may combine mid-sternal chest compressions (manual, mechanical), automated external defibrillators (AEDs), ventilation, and invasive procedures such as drug injection, implantable cardioverter defibrillators (IDCs), extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) or E-CPR, and cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB) [3-11]. Despite progress in CPR, out-of-hospital CA (OHCA) still results in a 30-day brain injury-free survival of approximately 2% [12-14]. Apart from E-CPR-which is still a work in progress—no CPR modalities can achieve the maintenance of metabolic processes before return of spontaneous circulation (ROSC) occurs. Difficulties encountered in achieving ROSC through CPR can be attributed to the pathophysiological challenges posed by the CA state, as summarized in Figure 1.

It is well known that ROSC occurs due to intracardiac action potentials, requiring at least 15 mmHg coronary perfusion pressure, which is provided by adequate blood volume (BV) dynamics, electrolytes, neurohumoral factors, and wall shear stresses [15]. Meanwhile, the arrested heart becomes almost empty due to massive shifts of BV to low-pressure zones, which increase the hepatosplanchnic venous capacitance. Additionally, the heart will be pulled even further away from the sternum by the cardiotorsal gravitational effect in the supine position. In addition, vigorous mid-sternal chest compressions, disregarding the biomechanics of the cylindrical ribcage—especially the orientations of the ribs and the axis of their movements—frequently lead CPR-related trauma [16].

Ultimately, performing CPR in a hemostatic condition induces an ineffective back-and-forth perfusion momentum.

As a result, most CPR survivors succumb to multi-organ failure shortly afterward, which can be attributed to inadequate organ perfusion during the procedure [17-20]. These shortcomings of CPR represent a significant burden for global health authorities, requiring a thorough analysis of the entire structure of CA.

In-depth glance at CA

Literally, CA defines an abrupt discontinuity of organ perfusion following sudden asystole of the systemic ventricle, whether fibrillated, dysfunctional due to cardiac–extracardiac events (e.g., myocardial injury or asphyxia), or knocked-out (e.g., the Zwaardemaker–Libbrecht effect) [21-26]. This means that, regardless of cardiac conditions, we must restore organ perfusion and metabolism as quickly as possible before irreversible cellular damage occurs [27]. In particular, the salvage of cellular metabolism—either with rapid ROSC or E-CPR—depends on microcirculations controlled by endothelial shear stress (ESS)-induced mediators [28]. Therefore, in this study, novel methods allowing for rational mobilization of the massive stagnant BV are presented, which can induce physiological pulse-pressure and, thus, ESS across the aorta.

These include proven methods employing invasive as well as non-invasive pulsatile mechanical circulatory support (MCS), which have been tested in beatless-heart and CA neonatal piglets, respectively [29-33]. In addition, a novel chest compression technique inducing an intracardiac hemorheological effect with adequate BV, thus promoting less traumatic ROSC, has recently been performed in two cases of drowning [34,35]. It is worth noting that this work does not replicate studies previously detailed in the literature. We highlight, through these existing studies, factors influencing the optimal restoration of tissue perfusion and metabolism; either through physiological or artificial circulatory driving forces.

In the absence of cardiac, respiratory, and muscular pumps along with peristaltic arteries and vascular tone, gravity remains the only exploitable driving force in the event of CA. A principle used for decades to drain venous return in CPB, typically overlooked in CPR, is considered in our study. Although the invasive MCS study involves surgery, making it impractical for OHCA, it provides evidence that ESS can restore endothelial function in beatless-heart circulation. The goal of this work is to corroborate the prioritization of ESS restoration as a potentially effective solution to improve microcirculation, hence mitigating the adverse effects typically associated with CPR. Specifically, the study aims to address factors that hinder rapid ROSC and the consequences of ESS suppression due to the continuous flow of E-CPR.

Materials and Methods

Novel concept

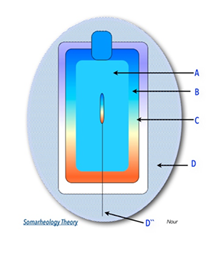

ESS-mediated endothelial functions generated by the cardiopulmonary pump through the closed, pressurized hydraulic left and right heart circuits are suppressed during CA. Practically, we may imagine the human body under the hydrostatic state of CA, as a container, consisting of an inner sphere (A) containing stagnant amounts of fluids (blood, air,) surrounded by a barrier sphere (B) of endothelium (vascular, alveolar), overlapped by an outer sphere (C) of covering layers (e.g., muscles, ribcage). As illustrated in (Figure 2), creating shear momentum across (A) to induce ESS at (B) can be achieved through direct intraluminal stimuli or indirect extraluminal impacts on (C) with pulsatile MCS (Somarheology theory) [29, 30].

A: amount of fluid (e.g. blood), B: barriers of cells (e.g. endothelium), and C: covering layers (e.g. muscles). D, D” = Device (MCS) inducing ESS via extracorporeal and intraluminal pulsatile impacts, respectively.

Studies

Details are available in the corresponding references of each study.

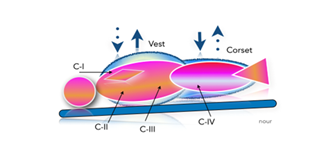

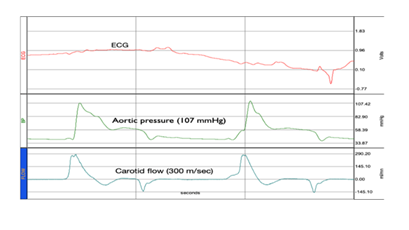

I)- As previously detailed in references [29,30], a non-invasive MCS composed of a multi-layer vest and corset driven by a low-pressure alternating pulsatile generator has been developed. Functionally, the device (depicted in Figure 3) can induce extracorporeal pulsatile impacts on several covering C-zones, circulating a massive amount of the stagnant BV in a regular rhythm. Prototypes have been tested in refractory CA models (≥20 min). The results showed significant hemodynamic improvements (as presented in Figure 4), with near-physiological AP (systolic AP ≥100mmHg) and improved cerebral perfusion, manifested by recovered carotid artery in echo-Doppler. In addition, laser flowmeter (Perimed PeriScan PIM 3 System) measurements from the tip of the tongue showed significant improvements in microcirculation. Furthermore, increased urine output and global vasodilation compensated with IV fluids (1–2 L) were observed. The TUNEL test revealed inferior apoptotic cells in the treated animal, along with obvious dilation of the intracardiac coronary bed.

Figure 3: Diagram illustrating the mechanism of CFR device wrapped around a manikin slightly tilted in the Trendelenburg position. Green arrows represent homogenous-circumferential alternating pulsations between Corset and Vest on several covering zone compartments (C) e.g., C-I (Mediastinal), C-II (parenchyma), C-III (diaphragm), and C-IV (Hepatosplanchnic).

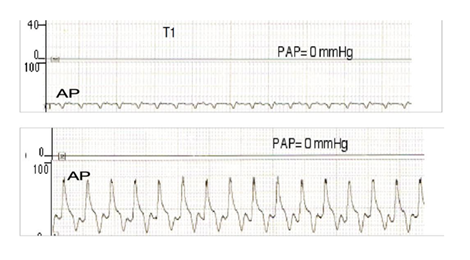

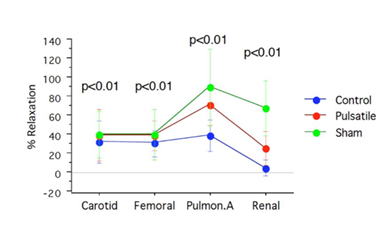

II)- Invasive MCS, presented in (Supplementary Figure 9) was tested as a pulsatile CPB versus conventional CPB in a beatless-heart model [31-33]. Fourteen neonatal piglets were divided into three groups: Group I (Gr-I, n=6) underwent pulsatile CPB at 100 bpm. Group II (Gr-II, n=6) underwent non-pulsatile CPB, with all subjects in these groups exposed to normothermic CPB for 120 minutes. A third sham group (n=2) was technically managed as in the other groups but without CPB. Hemodynamic, biochemical, and histopathological data were collected and compared between groups, including post-sternotomy insertion of right atrium, left atrium, left internal mammary, and intra-infundibular catheters for RAP, LAP, AP, and PAP measurements, respectively. Cardiac output (CO) was measured with a transit time probe temporarily placed around the PA (Transonic System Inc. Flowmeter). The cardiac index (CI), systemic vascular resistance index (SVRI), and pulmonary vascular resistance index (PVRI) were calculated according to the following formulae: SVRI= (mean AP-RAP)/CI X 79.9; PVRI= (mean PA-LAP)/CI X 79.9; CI=CO/Weight. Endothelial function and vasorelaxation (induced by acetylcholine and nitroprusside) were assessed in segments collected from the pulmonary artery (PA), carotid artery (CA), femoral artery (FA), and renal artery (RA) in all groups. Apoptosis was evaluated via TUNEL testing of myocardial and pulmonary tissue samples collected from all groups. Data collection points included before CPB (T0), at the start of CPB (T1), one hour after CPB (T2), and at the end of CPB (T3).

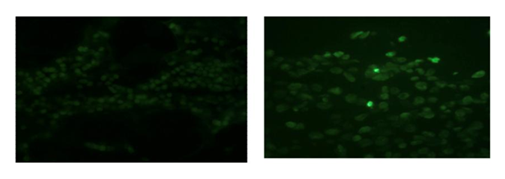

Results : As shown in (Figure 5), the device induced near-physiological AP (≥80mmHg) with a mean pulse-pressure of 46±7.55 mmHg in Gr-I versus 1.6±0.54 mmHg in the steady-flow Gr-II (P<0.05). The PAP was 0mmHg in both groups (beatless-heart). SVRI was 1.372±0.35 versus 3.140±0.344 dynes.s.cm-5/m2 in Gr-I versus Gr-II. PVRI was 0.3±0.06 versus 0.85±0.05 dynes.s.cm-5/m2 in Gr-I versus Gr-II (P<0.05). Unlike Gr-II, the acetylcholine reactivity test showed significant endothelial function restoration of endothelial function (almost closer to Sham) in Gr-I, as presented in Figure 6 and Table 1. The TUNEL test (Figure 7) revealed myocardial apoptotic cells in Gr-II, but none in Gr-I or Sham. Hemolysis was higher and lactic acid was lower in Gr-I versus Gr-II (p≤0.05).

Table 1 : Acetylcholine endothelial reactivity test results.

|

Arterial segments |

Sham |

Pulsatile CPB |

Control |

Acetylcholine |

|

Carotid |

40±24.4 |

39.4±27.6 |

32.3±22.03 |

|

|

Femoral |

40±26.7 |

39.3±15.6 |

30.6±14.2 |

% |

|

Pulmonary |

78±37.5 |

72.2±25.9 |

39.3±16.6 |

|

|

Renal |

67±28.9 |

26±17.7 |

5.3±8.7 |

Endothelial dependent vascular relaxation assessed via acetylcholine Test in 3 groups of newborn piglets who underwent pulsatile or conventional cardiopulmonary bypass (CPB), or Sham. P<0.01 (ANOVA test).

III)- Another novel technique called (3R/CPR), detailed in references [34, 35], involves chest compression at the fifth intercostal space while placing the victim in the left lateral decubitus position, with wrapped abdomen and slightly raised legs. The expected benefits include enabling the rescuer to bypass the sternal barrier, to refill the heart and bring it closer to the chest wall, then to recoil–rebound the near-cylindrical ribcage within the rules of thoracic biomechanics. Consequently, creating an intracardiac water hammer-like mechanism with adequate BV promotes hemorheological–biochemical reactions at the conducting system pacemaker cells, thereby ROCS in a less-traumatic manner.

Results the technique has recently been used unavoidably by a skilled lifeguard as a last-chance intervention in two drowning incidents after unsuccessful conventional CPR. ROSC occurred instantly with the refill maneuver in one victim, and after several recoil–rebound chest compressions in another victim despite CA ≥ 25 minutes, with ultimately severely depleted myocardial oxygen reserves and alcoholemia.

Discussion

The presented results demonstrate the feasibility and potential advantages of rapid CFR-inducing ESS in terms of significantly improving hemodynamics and microcirculation, regardless of return of heartbeats. Notably, successful ROSC in ≥70% of drowning victims and ≥90% of open-heart patients could be correlated with CFR-inducing intracardiac ESS with the lifeguard's Heimlich maneuver or CPB, respectively [36]. This phenomenon was also observed in our animal model study with shorter CA durations (≤8 minutes), resulting in immediate ROSC with the first abdominal corset pulsations. Similarly, we modeled the novel chest compression technique in order to create intracardiac ESS with adequate BV. Unlike CPR, this technique adapts to and overcomes the pathophysiological conditions of CA (Figure 1). Thus, it can promote rapid ROSC in complete harmony with thoracic biomechanics, thereby being less-traumatic to the victim and less exhausting for the rescuer. In addition, the rescuer can secure the victim's airway and easily check for heartbeats, in order to not confuse CA with syncope or cardiogenic shock. As stated by Feynman and demonstrated in our animal studies, ESS-mediated endothelial function must be induced, according to Newton’s principles, by maintaining an almost physiological arterial pulse-pressure [37]. In both studies, near-physiological AP was successfully induced in beatless-heart models—either invasively or non-invasively (e.g., with pulsatile MCSs)—in correspondence with cardiovascular biophysics and pathophysiological conditions.

For example, the right-heart circuit can adjust the pressurized BV and ESS at five different anatomical zones to maintain low-level remodeling [38]. Therefore, it is fundamental to maintain such low-level remodeling, as the delivery of ESS with high pulse-pressure can induce serious irreversible conditions (e.g., Eisenmenger syndrome) [39]. Therefore, in the first study, ESSs were delivered via alternating low-pressure pulsatile impacts on multiple C-zones on the right-heart-side; namely, at a rate of 40 bpm according to the capillary pressure cycle [40]. Regarding the left heart circuit, ESS inside the Valsalva sinuses determines the morphogenesis of coronary ostia and may contribute to severe hemodynamic deterioration [41, 42]. Accordingly, in the second study (invasive MCS), pulsatile impacts of ESS were delivered from the aortic root to minimize the development of intravascular vortices [43]. Remote induction of ESS from the aortic root can potentially endanger the blood vessel, making the device incompatible with E-CPR.

However, considerable hemolysis was observed in the treated group (Gr-I) due to the initial concept, which was subsequently addressed with a new device easy-to-use, and nearly-physiological as it adheres to the Bernoulli principle (Supplementary Figures 10 A and B) [33]. On the other hand, although the laws of physics have been employed with extreme efficiency and near-consistency in the cardiovascular field, probably since the Windkessel model [44], they are still disregarded by CPR. In particular, CPR overlooks the most fundamental principles of hydrostatic circuits, leading to illusory and inconclusive benefits for stroke victims. Oddly, most recent CPR-related publications have ignored previously reported fundamental hemostatic data showing flattened zero AP and central venous pressure (CVP) exceeding ≥80 mmHg during chest compressions [45,46]. Such severe hemostatic disorders can compromise the claimed benefits of invasive CPR procedures such as drug injections or ventilation due to a lack of interalveolar gas exchange [47].

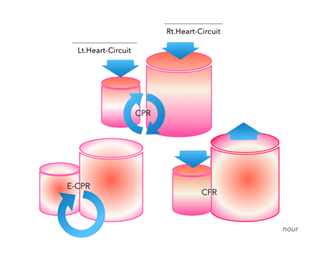

Figure 8 : Upper diagram simultaneous compression/decompression during CPR of incompressible hydrostatic fluid (blood) within the closed, pressurized, and disconnected (capillary circulation) right (Rt.) and left (Lt.) heart circuits. Lower right diagram circulatory flow restoration (CFR) via alternating extracorporeal compressions/decompressions in rhythmic impacts according to the capillary cycle. Lower left diagram the restored circulation with E-CPR.

As can be assumed from Figure 8, simultaneous compression/decompression of incompressible hydrostatic fluids (blood) inside closed and disconnected (capillary circulation) containers (i.e., the right and left cardiac circuits) creates a back-and-forth (yoyo) momentum.

We have therefore harnessed and intensified this constant biophysical phenomenon, which cannot be ignored, within the heart in the 3R/CPR method through the refill-recoil-rebound maneuvers. In the noninvasive MCS study, stagnant BVs were mobilized by alternately compressing and decompressing the supra-and infradiaphragmatic compartments, thereby inducing pulsatile circulatory flow (i.e., ESS) within the capillary cycle rhythm. Both studies rationally involve the gravitational effect, with a slight tilt in the Trendelenburg position. Furthermore, in both studies, the principle of circumferential (hoop) stress has been applied in accordance with the biomechanics of the near-cylindrical ribcage and trunk.

Considering other noninvasive MCSs used for CPR, we can identify the interposed abdominal compression (IAC-CPR) device [48]. This device consists of thoracic and abdominal plates that are linked by a stick to alternately compress the chest and abdomen during CA. However, the device designed to compress the abdominal aorta at high pressure must be closely monitored in order to avoid potential visceral ruptures. The device induces perpendicular longitudinal stress, instead of circumferential hoop stress in accordance with the cylindrical ribcage and trunk biomechanics. Furthermore, the device requires manpower, potentially fatiguing the rescuer.

The MAST suit is another high-pressure extracorporeal garment designed for fighter pilots, which can be used as a tourniquet in cases of infradiaphragmatic vascular trauma [49]. The proposal to use the MAST suit for CPR purposes was quickly abandoned, as it prevents tissue perfusion and cannot be deflated rapidly, resulting in irreversible cellular damage. In addition, the MAST suit is a static high-pressure tourniquet device that cannot promote ESS-mediated endothelial function. On the other hand, the application of the enhanced external counterpulsation (EECP) method resulted in improved brain perfusion in a post-arrest animal model [50]. The EECP is designed to compress the arterial blood flow in lower limbs during diastole, requiring the ROSC to be synchronized with heartbeats. Furthermore, the device employs high-pressure forces to affect the near-empty femoral arteries during CA, limiting its post-arrest application in adult patients.

Otherwise, the prompt employment of E-CPR is highly recommended in order to restore capillary circulation and rescue cellular metabolism, instead of exhorting ROSC through ineffective CPR perfusion [51]. Even so, E-CPR remains an invasive and time-consuming procedure requiring skilled personnel and ultrasound-guided installation through flattened arteries, which compromises its effectiveness in the context of OHCA. In addition, suppression of ESS by the constant flow of E-CPR creates a vicious emerging cycle of energy losses and endothelial dysfunction [32]. It is well known that endothelial dysfunction is commonly manifested in patients subjected to steady flow MCS (due to, e.g., postcardiotomy syndrome, post-hemodialysis inflammatory response) [52]. A phenomenon that could be aggravated by ROSC with E-CPR leading to severe countercurrent intravascular vortices (Reynolds stresses) [53].

This issue has been addressed in the invasive MCS study, demonstrating the significant restoration of endothelial function as confirmed by histopathological and biochemical results. In this study, endothelial dysfunction occurred under steady-flow CPB, despite maintaining myocardial perfusion via the coronary ostia of the unclamped (cross-clamped) aorta. Interestingly, as shown in Figure 6, although the PA endothelium was supposedly stunned due to no-flow perfusion in both groups, it was significantly preserved almost similarly to Sham in the pulsatile group. These results prove the crucial role of ESS in improving endothelial function via pulmonary collaterals and myocardial microcirculatory pathways. Evidence of restored endothelial function in vitro, as demonstrated in Table 1 and Figures 6 and 7, can significantly ameliorate the post-arrest multi-organ failure and mortality caused by poor CPR perfusion.

Strength and Limitations

The study exposes and attempts to address the CPR’s incapability to overcome the pathophysiological conditions of CA. These points have remained undisputed in the literature so-far. Compairing similar CPR modalities in Table 2 may clarify pros and cons of the study.

Table 2: Study proposal versus different CPR modalities:

Newton unit (1kg m/S2), SBP: systolic blood pressure, MAP: mean arterial blood pressure, *: Refractory and postarrest phases, ±: if available on-site, OHCA: Out-of-hospital-cardiac arrest, IHCA: In-hospital-cardiac arrest

As is known, the incidence of CA in the adult population is more frequent in young athletes with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) [54], and higher during the first month after myocardial infarction [55]. Accordingly, we created porcine models of cardiogenic shock with surgical LAD ligation, treated by ESS via different pulsatile MCSs. These studies revealed that CA occurred within ≤20 min after LAD ligation in piglets, compared to approximately 1h in adult pigs, likely due to immature myocardium. In addition, pigs have almost absent coronary collaterals [56], which is also confirmed by these studies as shown (Supplementary Figures 11). These elements may prove the robustness of the study, in particular the efficacy of MCS-induced ESS in newborn piglet models.

On the other hand, although the study received positive feedback, it reveals several limitations. First, the Materials and Methods section is shortened to avoid tedious repetition of published studies available in the literature. Second, the 3R/CPR method is still limited to two exceptional drowning incidents although it has been presented and published previously without any contradiction. This is primarily caused by the fierce strain in the present CPR doctrine, as well as a lack of animal models, given that its utility may not be fully reflected due to the great morphological discrepancies between species. For example, differences in cardiotorsal anatomy between species can compromise the efficacy of recoil–rebound maneuvers. According to the principles of thoracic biomechanics, chest compressions should be applied circumferentially in humans. Also, variations in the volumes and surfaces of stagnant BV zones affect the refilling maneuver; for example, porcine models present with larger hepatosplanchnic BV, when compared to humans and dogs. These factors were considered in our study of CA models, using various prototypes to address porcine–canine morphological differences.

Perspective

As E-CPR require installation by skilled professional squads who often intervene when the victim is in refractory CA, it is crucial to ensure organ perfusion with effective cardiac massage technique. This highlights the potential for further investigations on 3R/CPR. In view of the well-known and unnecessarily high mortality in CA models, future studies comparing the benefits of 3R/CPR and non-invasive MCS with CPR should be conducted using angiographic technology on cadavers, as well as computational models [57, 58].

Conclusion

Adequate organs perfusion during CPR remains elusive. Alternatively, mechanical ESS restoration, regardless of heartbeat return, as well as 3R/CPR, have shown promising potentials in these early stages warranting further investigation to improve the dismal outcomes of CA.

Declarations

Competing interests: We certify that there are no conflict of interests to disclose.

Ethical Approval: Not applicable. Although two drowning incidents were referenced in the study, they were conducted by a competent rescuer as a last-chance intervention after unsuccessful CPR, providing data anonymously without revealing the victims’ identities.

Clinical trial numbers: Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement: Not applicable.

Author Contributions Statement: S.N. conceived, patented, developed the concept, designed and conducted the experimental studies, and wrote the corresponding publications.

Funding: Nothing to declare.

Using artificial intelligence chatbots: None.

Data: Available upon reasonable request.

Acknowledgments: We thank our Colleagues and Cardiovascular Researchers from Sun Yat Sen University, GZ, China; HEGP and Marie-Lannelongue Hospitals, Universities of Paris, France.

Reference

- Sandroni C, Cronberg T, Sekhon M. Brain injury after cardiac arrest: pathophysiology, treatment, and prognosis. Intensive Care Med 47 (2021): 1393-1414.

- Toy J, Friend L, Wilhelm K, et al. Evaluating the current breadth of randomized control trials on cardiac arrest: A scoping review. J Am Coll Emerg Physicians Open 5 (2024): e13334.

- Truong HT, Low LS, Kern KB, et al. Current approaches to cardiopulmonary resuscitation. Curr Probl Cardiol 40 (2015): 275–313.

- Peberdy MA, Gluck JA, Ornato JP, et al. Cardiopulmonary resuscitation in adults and children with mechanical circulatory support: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation 135 (2017): e1115–e1134.

- Homma PCM, de Graaf C, Tan HL, et al. Transfer of essential AED information to treating hospital (TREAT). Resuscitation 149 (2020): 47–52.

- Deakin CD, Koster RW, et al. Chest compression pauses during defibrillation attempts. Curr Opin Crit Care 22 (2016): 206–211.

- van Eijk JA, Doeleman LC, Loer SA, et al. Ventilation during cardiopulmonary resuscitation: a narrative review. Resuscitation 203 (2024): 110366.

- Kubo A, Hiraide A, Shinozaki T, et al. Impact of epinephrine on neurological outcomes in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest after AED use in Japan. Sci Rep 15 (2025): 274.

- Morton MB, Mariani JA, Kistler PM, et al. Transvenous versus subcutaneous implantable cardioverter defibrillators in young cardiac arrest survivors. Intern Med J 53 (2023): 1956–1962.

- Kobayashi RL, Gauvreau K, Alexander PMA, et al. Higher survival with extracorporeal cardiopulmonary resuscitation compared with conventional CPR in children following cardiac surgery. Crit Care Med 52 (2024): 563–573.

- Sawamoto K, Tanno K, Takeyama Y, et al. Successful treatment of severe accidental hypothermia with prolonged cardiac arrest using cardiopulmonary bypass: a case report. Int J Emerg Med 5 (2012): 9.

- Yan S, Gan Y, Jiang N, et al. Global survival rate among adult out-of-hospital cardiac arrest patients receiving CPR: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Crit Care 24 (2020): 61.

- Rubertsson S, Lindgren E, Smekal D, et al. Mechanical chest compressions and simultaneous defibrillation vs conventional CPR in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: the LINC randomized trial. JAMA 311 (2014): 53–61.

- Kumar A, Avishay DM, Jones CR, et al. Sudden cardiac death: epidemiology, pathogenesis and management. Rev Cardiovasc Med 22 (2021): 147–158.

- Reynolds JC, Salcido DD, Menegazzi JJ, et al. Coronary perfusion pressure and return of spontaneous circulation after prolonged cardiac arrest. Prehosp Emerg Care 14 (2010): 78–84.

- Arbogast KB, Maltese MR, Nadkarni VM, et al. Thoracic force-deflection characteristics measured during CPR: comparison with post-mortem human data. Stapp Car Crash J 50 (2006): 131–145.

- Panchal AR, Bartos JA, Cabañas JG, et al. Part 3: Adult basic and advanced life support: 2020 AHA guidelines for CPR and emergency cardiovascular care. Circulation 142 (2020): S366–S468.

- Berg KM, Cheng A, Panchal AR, et al. Part 7: Systems of care: 2020 AHA guidelines for CPR and ECC. Circulation 142 (2020): S580–S604.

- Oeser C, et al. Cardiac resuscitation: continuous chest compressions do not improve outcomes. Nat Rev Cardiol 13 (2016): 5.

- Srinivasan NT, Schilling RJ, et al. Sudden cardiac death and arrhythmias. Arrhythm Electrophysiol Rev 7 (2018): 111–117.

- de Noronha SV, Sharma S, Papadakis M, et al. Aetiology of sudden cardiac death in athletes in the United Kingdom. Heart 95 (2009): 1409–1414.

- Link MS, et al. Mechanically induced sudden death in chest wall impact (commotio cordis). Prog Biophys Mol Biol 82 (2003): 175–186.

- Thygesen K, Uretsky BF, et al. Acute ischaemia as a trigger of sudden cardiac death. Eur Heart J 6 (2004): D88–D90.

- Deshpande SR, Herman HK, Quigley PC, et al. Arrhythmogenic right ventricular cardiomyopathy/dysplasia: review of 16 pediatric cases and proposal of modified pediatric criteria. Pediatr Cardiol 37 (2016): 646–655.

- Surawicz B, Gettes LS, et al. Two mechanisms of cardiac arrest produced by potassium. Circ Res 12 (1963): 415–421.

- Donoghue AJ, Nadkarni V, Berg RA, et al. Out-of-hospital pediatric cardiac arrest: epidemiologic review. Ann Emerg Med 46 (2005): 512–522.

- van Empel VP, Bertrand AT, Hofstra L, et al. Myocyte apoptosis in heart failure. Cardiovasc Res 67 (2005): 21–29.

- Manning D, Rivera EJ, Santana LF, et al. Capillary life cycle: angiogenesis and microvascular rarefaction. Vascul Pharmacol 156 (2024): 107393.

- Nour S, Carbognani D, Chachques JC, et al. Circulatory flow restoration versus CPR: a new therapeutic approach in sudden cardiac arrest. Artif Organs 41 (2017): 356–366.

- Nour S, et al. Endothelial shear stress enhancements in critically ill COVID-19 patients. Biomed Eng Online 19 (2020): 91.

- Nour S, et al. Pulsatile vs conventional pediatric CPB: study in piglets. University of Paris XI (2003).

- Nour S, et al. Shear stress and energy losses in pediatric heart–lung machines. Proc Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Surg Meeting (2008): 1–4.

- Nour S, Liu J, Dai G, et al. Shear stress, energy losses, and costs in pulsatile cardiac assist devices. Biomed Res Int 2014 (2014): 651769.

- Nour S, et al. Time to resuscitate CPR: the 3R/CPR concept. Cardiol Angiol Int J 11 (2022): 363–375.

- Tsoungani G, Nour S, et al. Application of 3R chest compression technique in CPR: two-case report. Arch Acad Emerg Med 13 (2025): e30.

- Heimlich HJ, et al. Subdiaphragmatic pressure to expel water in drowning. Ann Emerg Med 10 (1981): 476–480.

- Feynman RP, Leighton RB, Sands M, et al. The Feynman Lectures on Physics, Vol 1. Pearson/Addison-Wesley (2005).

- Nour S, Zhensheng Z, Wu G, et al. Driving forces in right heart failure: new concept and device. Asian Cardiovasc Thorac Ann 17 (2009): 525–530.

- D'Alto M, Vizza CD, Romeo E, et al. Long-term effects of bosentan in Eisenmenger physiology. Heart 93 (2007): 621–625.

- Mueller M, Holzer M, Losert H, et al. Capillary refill time and ROSC in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. Crit Care 29 (2025): 37.

- Nour S, Dai G, Carbognani D, et al. Intrapulmonary shear stress enhancement in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Pediatr Cardiol 33 (2012): 1332–1342.

- Hutchins GM, Kessler-Hanna A, Moore GW, et al. Development of coronary arteries in the embryonic heart. Circulation 77 (1988): 1250–1257.

- Nour S, et al. Flow and rate: a new hemodynamic theory. In: Biophysics. Intech, Rijeka (2012): 1–62.

- Frank O. Die Grundform des arteriellen Pulses. Z Biol 37 (1899): 483–526.

- Putzer G, Martini J, Spraider P, et al. Adrenaline improves cerebral blood flow during CPR in a porcine model with extracorporeal support. Resuscitation 168 (2021): 151–159.

- Swenson RD, Weaver WD, Niskanen RA, et al. Hemodynamics in humans during conventional and experimental CPR. Circulation 78 (1988): 630–639.

- Perkins GD, Ji C, Deakin CD, et al. A randomized trial of epinephrine in out-of-hospital cardiac arrest. N Engl J Med 379 (2018): 711–720.

- Babbs CF, et al. Interposed abdominal compression CPR: evidence-based review. Resuscitation 59 (2003): 71–82.

- Lilja GP, Clinton J, Mahoney B, et al. MAST usage in CPR. Ann Emerg Med 13 (1984): 833–835.

- Hu CL, Liu R, Liao XX, et al. Enhanced external counterpulsation improves neurological recovery after ROSC in dog model. Crit Care Med 41 (2013): e62–e73.

- Pound G, Eastwood GM, Jones D, et al. Potential role of E-CPR during in-hospital cardiac arrest in Australia. Crit Care Resusc 25 (2023): 90–96.

- Jofré R, Rodriguez-Benitez P, López-Gómez JM, et al. Inflammatory syndrome in hemodialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 17 (2006): S274–S280.

- Jones SA, et al. Relationship between Reynolds stresses and viscous dissipation: implications for red cell damage. Ann Biomed Eng 23 (1995): 21–28.

- Spirito P, Binaco I, Poggio D, et al. Role of CMR in planning septal myectomy in obstructive HCM. Am J Cardiol 123 (2019): 1517–1526.

- Solomon SD, Zelenkofske S, McMurray JJ, et al. Sudden death after MI with LV dysfunction or HF. N Engl J Med 352 (2005): 2581–2588.

- Gorge G, Schmidt T, Ito BR, et al. Microvascular adaptation in swine hearts with coronary stenosis. Basic Res Cardiol 84 (1989): 524–535.

- Wei J, Tung D, Sue SH, et al. CPR in prone position: simplified outpatient method. J Chin Med Assoc 69 (2006): 202–206.

- Jamaludin FH, Fathil SM, Wong TW, et al. Simulation of protective barrier enclosure for CPR. Resusc Plus 8 (2021): 100180.