The Value of Rigid Cervical Orthesis After Fixation and Fusion of Degenerative Cervical Spine in Geriatric Patients

Dittmer†1, L. Khalafov†1, T. Lampmann1, H. Asoglu1, M. Janijc1, Z. Kiseleva1, H. Alenezi1, M. Hamed1, H. Vatter1, M. Banat1*

1Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Bonn, Bonn, Germany

†contributed equally to this work

*Corresponding Author: Mohammed Banat, M.D, Department of Neurosurgery, University Hospital Bonn Venusberg-Campus 1, Building 81, 53127 Bonn, Germany.

Received: 21 November 2025; Accepted: 03 December 2025; Published: 20 January 2026

Article Information

Citation: J. Dittmer, L. Khalafov, T. Lampmann1, H. Asoglu, M. Janijc, Z. Kiseleva, H. Alenezi, M. Hamed1, H. Vatter, M. Banat. The Value of Rigid Cervical Orthesis After Fixation and Fusion of Degenerative Cervical Spine in Geriatric Patients. Journal of Spine Research and Surgery. 8 (2026): 01-06.

Share at FacebookAbstract

Introduction:

The use of a cervical orthosis after fixation and fusion of the cervical spine in geriatric patients is still controversial. The aim of this study was to find out whether cervical orthosis had an influence on early postoperative clinical-neurological and radiological outcomes.

Methods:

We included and analyzed the data of all geriatric patients who were surgically treated at our spine center for symptomatic degenerative cervical spine disease requiring ventral and/or dorsal fixation with fusion. From 2010 to 2012, the patients received a rigid cervical orthosis postoperatively (group 1); from 2012 to 2014, no orthosis was applied (group 2). All patients were evaluated 3 months after surgery as part of their clinical follow-up. Radiographic and clinical scores were recorded before and after the operation. Postoperative complications within 30 days of the initial surgery were analyzed.

Results:

A total of 84 patients were included, of which 65.5% received postoperative cervical orthosis. Patients with orthosis were significantly younger (p=0.009) and had lower ASA scores (p=0.007) than those in group 2. The clinical and radiologic parameters were similar in both groups but without statistical significance, especially with regard to numeric rating scale (NRS) and neck disability index (NDI) scores. However, it was relevant that the patients with an orthosis did not tolerate it well and developed complications (p <0.001).

Conclusions:

Postoperative cervical orthosis did not lead to improved early clinical and radiological outcomes but were associated with devicerelated complications.

Keywords

Cervical spine; geriatric patients; spinal instrumentation; rigid cervical orthosis; degenerative spine disease; postoperative complications; neck pain

Article Details

Introduction

The use of cervical collars is common after cervical spine surgery: almost 50% of surgeons apply a soft collar after one-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion (ACDF) and up to 70% apply a rigid orthosis after two-level ACDF [1]. There are no clear data defining the optimal duration of postoperative external bracing, although collars are usually applied for 3 to 13 weeks after surgery [1, 2]. There is no consensus in the literature on whether or not to use an orthosis, as there is a lack of randomized studies [3-5]. Some studies investigate the necessity of cervical collars after ventral cervical spine fusion, these studies showing no benefit of additional orthosis after ACDF [4-6]. Other authors recommend the use of orthoses after spinal interventions on the cervical spine in the case of traumatic injury [6-10]. However, the use of orthoses is not without consequences in some patients, as shown by studies on traumatic injuries to the cervical spine [6, 8, 10].

Opposition to such orthoses after surgical stabilization of injured cervical vertebrae and head trauma is based on the fact that a significant elevation of intracranial pressure has been found due to the increase in jugular pressure [11].

The aim of this study was to find out whether the application of a cervical orthosis after ventral and/or dorsal fusion and stabilization was necessary in degenerative cervical spine disease in geriatric patients, and whether this had an influence on clinical and radiological parameters in the short term after surgery.

Material and methods

Patient selection and inclusion criteria

This retrospective single center cohort study evaluated postoperative management, clinical and radiological information in geriatric patients at our spine center after spinal posterior and/or ventral open instrumentation and fusion with or without postoperative cervical orthosis.

All geriatric patients aged ≥65 treated between 2010 and 2014 for degenerative cervical spine disease requiring neurosurgical treatment were included in this analysis.

Up until 2012 our standard postoperative management approach was to apply a rigid cervical orthosis to every patient after instrumentation. From that year onwards, we changed the procedure and discharged patients to home care without a cervical orthosis.

Over the 4 years from 2010 to 2014 all patients were called in for a regular outpatient follow-up appointment after 12 weeks. Computed tomography (CT) scans of the cervical spine were performed on all patients immediately after the operation and at the 12 week follow-up.

Patients’ clinical information including age, sex, ASA score, BMI, length of stay in days, history of cardiovascular comorbidities, duration of operation, number of affected vertebrae, and approach, as well as surgery-related complications and in-hospital complications, was registered and documented. Early postoperative complications were assessed using a publicly available list from the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality and the Center for Medicare and Medicaid Services. They are referred to as patient safety indicators (PSIs) and hospital-acquired conditions (HACs) [12-14]. Data from the pre- and postoperative CT scans were considered [5]. For additional data on clinical outcomes, we assessed the numeric rating scale (NRS) and neck disability index (NDI) scores preoperatively and at 3 months postoperatively.

Surgical procedure

Indication criteria for neurosurgical treatment were symptomatic cervical spinal canal stenosis with spondylolisthesis and degenerative disc disease. Patients also had cervical myelopathy. They had symptoms such as neck and/or arm pain. The decision for dorsal or ventral neurosurgical treatment was made by the surgeon using clinical judgement and referring to the pathology report. In order to avoid any potential bias caused by the surgical approach, we included it in our statistical analysis.

The primary endpoint of the study was the influence of the orthosis on clinical and radiological parameters after 3 months compared to the group without a cervical orthosis.

Exclusion criteria were incomplete data and patients with other spinal pathologies (infection, tumor, fracture).

Radiological evaluation

Postoperative CT imaging data of the cervical spine from the patients’ follow-up appointments were analyzed by an independent neuroradiologist. Abnormalities and signs of instability or fusion/non-fusion were evaluated and documented.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using IBM® SPSS® Statistics V22.0 (IBM, Chicago, Illinois, USA). Quantitative, normally distributed data are presented as mean values ± standard deviation (SD), while non-parametric data are summarized by median values [first quartile – third quartile]. Nominal data were analyzed by applying the independent t-test (two-sided) or, if expected frequencies were <5, Fisher’s exact test (two-sided). Data were described as means with standard deviation (SD) and frequency (n). A p value <0.05 was considered significant. Univariate analysis was carried out. We also analyzed the correlation between cervical orthosis and clinical as well as radiological parameters.

Results

We identified 100 patients who had undergone neurosurgical treatment at our level 1 center for spinal surgery. A total of 84 patients met the inclusion criteria and were included in the analysis, with 55 (65.5%) receiving a postoperative cervical orthosis (group 1) and 29 (34.5%) not receiving an orthosis (group 2).

Patients in group 1 were significantly younger (p=0.009) and more frequently had lower ASA scores (p=0.007). No significant differences were observed between the groups regarding sex distribution, BMI, length of hospital stay, comorbidity burden using the Charlson comorbidity index (CCI), duration of operation, or the number of stabilized levels. Table 1 gives more details.

Table 1: Univariate analysis of patient characteristics and procedures, using Fisher’s exact test (two-sided) and independent t-test.

|

Total (N=84) |

w. Orthosis group |

w/o Orthosis group |

P value |

||

|

No. of patients |

55 (56.5%) |

29 (34.5%) |

|||

|

Age (yrs.), median [q1-q3] |

72 [68-79] |

76 [73-82] |

0.009* |

||

|

SEX |

0.339 |

||||

|

Female |

23 (42%) |

9 (31%) |

|||

|

Male |

32 (58%) |

20 (69%) |

|||

|

BMI, kg/m2, median [q1-q3] |

26 [24-27] |

25 [24-27] |

0.95 |

||

|

ASA-Score |

0.007* |

||||

|

1&2 |

19 (34.5%) |

3 (10.3%) |

|||

|

3&4 |

36 (65.5%) |

26 (89.7%) |

|||

|

Length of stay in days, median [1-3q] |

14.0 [11.0-20.0] |

13.0 [10.0-23.5] |

0.95 |

||

|

CCI Score, median [q1-q3] |

6.0 [4.0-8.0] |

6.0 [4.0-8.0] |

0.823 |

||

|

Duration of operation in min. |

205.0 [152.0-267.0] |

211.0 [179.0-253.0] |

0.797 |

||

|

Stabilized level |

0.179 |

||||

|

1-2 Level |

12 (22%) |

8 (27%) |

|||

|

>/= 3 Levels |

43 (78%) |

21 (73%) |

|||

|

approach |

0.064 |

||||

|

ventral |

17 |

7 |

|||

|

dorsal |

33 |

20 |

|||

|

combined |

5 |

2 |

|||

|

Surgery-related complications |

0.848 |

||||

|

Temporary. neurological deficit |

2 (3.6%) |

1 (3.4%) |

|||

|

Cerebrospinal fistula |

2 (3.6%) |

1 (3.4%) |

|||

|

Wound infection |

3 (5.5%) |

1 (3.4%) |

|||

|

Disturbance of wound healing |

2 (3.6%) |

2 (6.8%) |

|||

|

In-hospital complications |

0.834 |

||||

|

Pneumonia |

2 (6.0%) |

1 (2.1%) |

|||

|

UTI |

1 (1.8%) |

2 (4.3%) |

|||

|

Material failure/dislocation after 3 months |

1 (1.8%) |

1 (2.1%) |

0.476 |

||

|

NRS neck, median [q1-q3] |

|||||

|

Pre surgery |

7 [6-9] |

6 [6-8] |

0.08 |

||

|

3 months after surgery |

5 [3-6] |

4 [2-5] |

0.057 |

||

|

NRS arm, median [q1-q3] |

|||||

|

Pre surgery |

7 [6-9] |

7 [6-8] |

0.377 |

||

|

3 months after surgery |

4 [4-6] |

4 [2-6] |

0.49 |

||

|

NDI, median [q1-q3] |

0.552 |

||||

|

Pre-operative |

80 [70-90] |

60 [40-70] |

|||

|

3 months after surgery |

60 (40-70) |

60 [50-70] |

|||

|

Orthosis complications |

<0.001* |

||||

|

Swallowing disorder |

4 (7%) |

0 |

|||

|

Pressure sores |

5 (9%) |

0 |

|

Categorical variables are shown as number (%) and continuous variables as median [interquartile ranges]. AEs: Adverse events. BMI: Body mass index. min.: Minutes. NRS: Numerical rating scale. q1-q3: First quartile-third quartile. UTI: urinary tract infection.* p≤0.05: statistically significant.

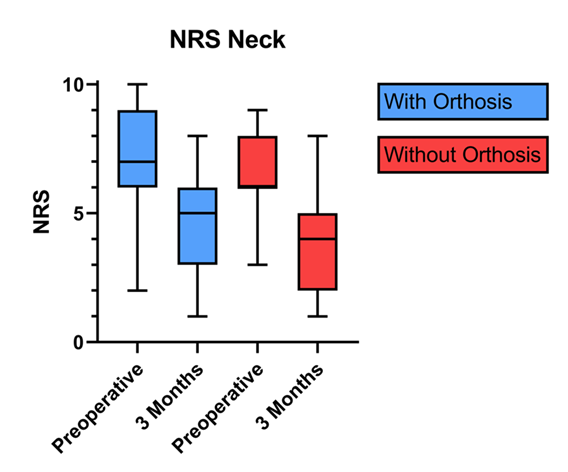

The NRS score for neck pain was similarly distributed in both groups. After 3 months, there was a trend towards less pain in group 2 without an orthosis, but this trend was not statistically significant (p=0.057), see Figure 1.

Figure 1: (Box and whiskers): Numerical rating scale (NRS) for pre- and postoperative neck pain in both groups. The 25th and 75th percentiles of the data define the box portion. The line inside the box is the median (the 50th percentile). The mean is identified as (+) and the whiskers are defined by the 10th and 90th percentiles.

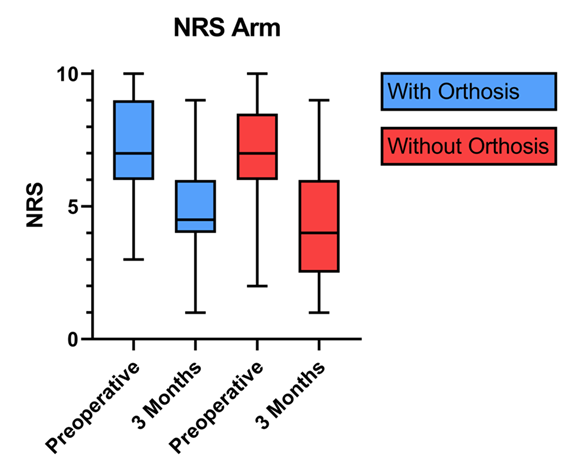

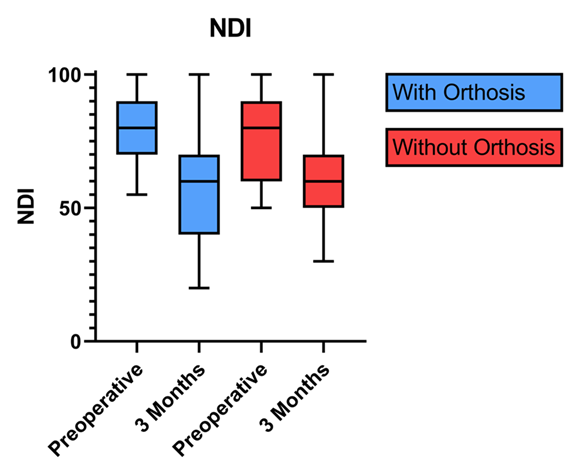

The NRS score for arm pain and the NDI did not differ significantly between the groups. There was no statistical significance and the values were equally distributed – see Figure 2 and Figure 3.

Figure 2: (Box and whiskers): Numerical rating scale (NRS) for pre- and postoperative arm pain in both groups. The 25th and 75th percentiles of the data define the box portion. The line inside the box is the median (the 50th percentile). The mean is identified as (+) and the whiskers are defined by the 10th and 90th percentiles.

Figure 3: (Box and whiskers): Neck disability index (NDI) pre- and postoperatively in both groups. The 25th and 75th percentiles of the data define the box portion. The line inside the box is the median (the 50th percentile). The mean is identified as (+) and the whiskers are defined by the 10th and 90th percentiles.

The main message of our results is that the patients in group 1 tolerated the cervical orthosis very poorly. Many showed pressure sores on the chin and some patients reported regular dysphagia, while the patients in group 2 did not have these complaints (p<0.001).

Another important feature of our results is that we saw no material failure in either group, although an evaluation after 3 months is too early to come to a definitive conclusion.

Discussion

The application of rigid cervical orthoses after degenerative cervical spine surgery remains an individual decision to this day [1]. The aim of the study was to find out to what extent a cervical orthosis was necessary after ventral or dorsal stabilization in geriatric patients, and whether wearing an orthosis had an influence on the early postoperative course or not.

There is a clear recommendation for treatment with cervical orthoses for certain pathologies in geriatric patients, such as fractures of the cervical spine in the conservative approach, or as an add-on for surgical treatment [15, 16]. Other scientific studies report that treatment with cervical orthoses is associated with frequent complications [17]. Baird's working group concludes that wearing an orthosis after two-level segmental stabilization and fusion from the ventral side is superfluous, without specifically addressing age or indication [4].

The aim of surgical treatment of symptomatic cervical spinal canal stenosis in older patients is to improve quality of life and prevent further impairment, irrespective of whether the supply is from the ventral or dorsal side [18-20]. Some scientific studies address the benefits to patients of surgical treatment for degenerative changes in the cervical spine [21]. However, few studies describe both the surgical treatment and the wearing of a cervical orthosis in geriatric patients in more detail. The question now also arises as to whether the cervical orthosis has an influence on the revision rate or the neurological-clinical outcome. There is no valid answer to this question in the literature; some reasons for revision in the event of material failure are described, but few in connection with a cervical orthosis [22, 23].

One study recommends carrying out a perioperative evaluation in geriatric patients in order to measure success, whether a cervical orthosis was applied or not [24]. Our data support this conclusion,

Finally, our data and an extensive search of the literature show that the application of a cervical orthosis after surgical treatment of the cervical spine in geriatric patients does not provide any additional benefit in either the short or the long term.

Limitations

Our study has several limitations. The retrospective nature of this single center cohort study harbors the risk of potential unmasked selection bias. Small patient numbers in some subgroups may have affected the statistical evaluation. Because of this, a larger number of patients should be included in future to check whether our conclusions were biased.

Conclusion

In this cohort of geriatric patients undergoing cervical stabilization and fusion, the use of postoperative cervical orthosis was not associated with better early clinical or functional outcomes but led to device-related complications. Given the lack of clinical benefit and the increased risk of adverse events, the routine application of cervical orthoses in this context should be reconsidered.

Declarations

Ethical approval:

All of the procedures performed were in line with the ethical standards of our institutional and national research committee (Ethics committee of the Rheinische Friedrich Wilhelms University Bonn) and with the 1964 Helsinki declaration and its later amendments or comparable ethical standards. The local ethics committee at the University of Bonn approved this study (protocol no. 067/21).

Availability of data and material:

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this published article.

Conflict of interest:

The authors report no conflicts of interest. The authors alone are responsible for the content and writing of this work.

Consent to participate:

'Not applicable' for that section.

Consent for publication:

The Corresponding Author transfers to the journal the non-exclusive publication rights and he warrants that his contribution is original and that he has full power to make this grant. The author signs for and accepts responsibility for releasing this material on behalf of any and all co-authors. This transfer of publication rights covers the non-exclusive right to reproduce and distribute the article, including reprints, translations, photographic reproductions, microform, electronic form (offline, online) or any other reproductions of similar nature.

Funding statement:

This research received no external funding.

Acknowledgement:

None.

References

- Bible, J.E., et al., Postoperative bracing after spine surgery for degenerative conditions: a questionnaire study. Spine J 9 (2009): p. 309-316.

- Schultz, K.D., Jr., et al., Single-stage anterior-posterior decompression and stabilization for complex cervical spine disorders. J Neurosurg 93 (2000): p. 214-221.

- Campbell, M.J., et al., Use of cervical collar after single-level anterior cervical fusion with plate: is it necessary? Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 34 (2009): p. 43-8.

- Baird, E.O., et al., Do You Need to Use a Collar After a 2-level Instrumented ACDF? J Spinal Disord Tech 28 (2015): p. 199-201.

- Jagannathan, J., et al., Radiographic and clinical outcomes following single-level anterior cervical discectomy and allograft fusion without plate placement or cervical collar. J Neurosurg Spine 8 (2008): p. 420-428.

- Karason, S., et al., Evaluation of clinical efficacy and safety of cervical trauma collars: differences in immobilization, effect on jugular venous pressure and patient comfort. Scand J Trauma Resusc Emerg Med 22 (2014): p. 37.

- Sundstrom, T., et al., Prehospital use of cervical collars in trauma patients: a critical review. J Neurotrauma 31 (2014): p. 531-40.

- Liew, S.C. and D.A. Hill, Complication of hard cervical collars in multi-trauma patients. Aust N Z J Surg 64 (1994): p. 139-140.

- Kolb, J.C., R.L. Summers, and R.L. Galli, Cervical collar-induced changes in intracranial pressure. Am J Emerg Med 17 (1999): p. 135-7.

- James, C.Y., et al., Comparison of Cervical Spine Motion During Application Among 4 Rigid Immobilization Collars. J Athl Train 39 (2004): p. 138-145.

- Mobbs, R.J., M.A. Stoodley, and J. Fuller, Effect of cervical hard collar on intracranial pressure after head injury. ANZ J Surg 72 (2002): p. 389-91.

- Al-Tehewy, M.M., et al., Association of patient safety indicator 03 and clinical outcome in a surgery hospital. Int J Health Care Qual Assur, 2020. ahead-of-print(ahead-of-print).

- Stocking, J.C., et al., Postoperative respiratory failure: An update on the validity of the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality Patient Safety Indicator 11 in an era of clinical documentation improvement programs. Am J Surg 220 (2020): p. 222-228.

- Horn, S.R., et al., Hospital-acquired conditions occur more frequently in elective spine surgery than for other common elective surgical procedures. J Clin Neurosci 76 (2020): p. 36-40.

- Melin, D.A., E.D. Rich, and S.J. Despins, Challenges of Treating a C2 Odontoid Fracture in an Elderly Patient With Multiple Comorbidities: A Case Report. Cureus 16 (2024): p. e75242.

- Schroeder, G.D., et al., A Systematic Review of the Treatment of Geriatric Type II Odontoid Fractures. Neurosurgery 77 (2015): p. S6-14.

- Moran, C., et al., Understanding post-hospital morbidity associated with immobilisation of cervical spine fractures in older people using geriatric medicine assessment techniques: A pilot study. Injury 44 (2013): p. 1838-1842.

- Williams, J., et al., Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy: Evaluation and Management. Orthop Clin North Am 53 (2022): p. 509-521.

- Ghogawala, Z., et al., Effect of Ventral vs Dorsal Spinal Surgery on Patient-Reported Physical Functioning in Patients With Cervical Spondylotic Myelopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA 325 (2021): p. 942-951.

- Choi, J.H., et al., A Comparison of Short-Term Outcomes after Surgical Treatment of Multilevel Degenerative Cervical Myelopathy in the Geriatric Patient Population: An Analysis of the National Surgical Quality Improvement Program Database 2010-2020. Asian Spine J 18 (2024): p. 190-199.

- Shahi, P., et al., NDI <21 Denotes Patient Acceptable Symptom State After Degenerative Cervical Spine Surgery. Spine (Phila Pa 1976), 48 (2023): p. 766-771.

- You, J., et al., Factors predicting adjacent segment disease after anterior cervical discectomy and fusion treating cervical spondylotic myelopathy: A retrospective study with 5-year follow-up. Medicine (Baltimore), 2018. 97(43): p. e12893.

- Koerner, J.D., C.K. Kepler, and T.J. Albert, Revision surgery for failed cervical spine reconstruction: review article. HSS J 11 (2015): p. 2-8.

- Goudihalli, S.R., et al., Spine Surgery in a Geriatric Population. Is it Really Different? Neurol India 72 (2024): p. 345-351.